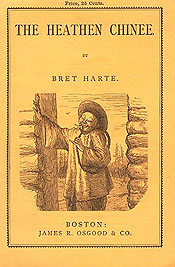

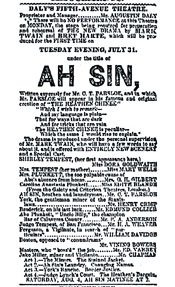

When MT and Bret Harte agreed in the fall of 1876 to collaborate on a play set in a Calaveras County mining camp and featuring a "Chinaman" named Ah Sin, it must have seemed like a sure bet. They were two of the country's most popular authors, having conquered the eastern reading public as "humorists of the Pacific slope." MT rose to fame in 1865 on the back of a Calaveras miner's celebrated jumping frog, and Harte's 1870 poem about a character named Ah Sin, published as "Plain Language from Truthful James" but soon famous as "The Heathen Chinee," made him "the most celebrated man in America to-day," as MT nervously noted in a 3 March 1871 letter. Five years later Harte's star had lost some of its shine, but MT's was burning even more brightly. This is probably what led Harte to propose the collaboration. The steady royalty checks that MT was receiving at that time from John Raymond's performances as Colonel Sellers, apparent proof that playwriting was the best way to get rich, made him willing to say Yes. Charles Parsloe, the white actor both authors had in mind to play Ah Sin, had already made a hit with theater-goers in the small part of Hop Sing in an 1876 dramatization of Harte's Two Men of Sandy Bar. As MT wrote his friend William Dean Howells just before he and Harte starting writing, "This Chinaman is to be the character of the play, & both of us will work on him & develop him." When MT and Bret Harte agreed in the fall of 1876 to collaborate on a play set in a Calaveras County mining camp and featuring a "Chinaman" named Ah Sin, it must have seemed like a sure bet. They were two of the country's most popular authors, having conquered the eastern reading public as "humorists of the Pacific slope." MT rose to fame in 1865 on the back of a Calaveras miner's celebrated jumping frog, and Harte's 1870 poem about a character named Ah Sin, published as "Plain Language from Truthful James" but soon famous as "The Heathen Chinee," made him "the most celebrated man in America to-day," as MT nervously noted in a 3 March 1871 letter. Five years later Harte's star had lost some of its shine, but MT's was burning even more brightly. This is probably what led Harte to propose the collaboration. The steady royalty checks that MT was receiving at that time from John Raymond's performances as Colonel Sellers, apparent proof that playwriting was the best way to get rich, made him willing to say Yes. Charles Parsloe, the white actor both authors had in mind to play Ah Sin, had already made a hit with theater-goers in the small part of Hop Sing in an 1876 dramatization of Harte's Two Men of Sandy Bar. As MT wrote his friend William Dean Howells just before he and Harte starting writing, "This Chinaman is to be the character of the play, & both of us will work on him & develop him."

| |

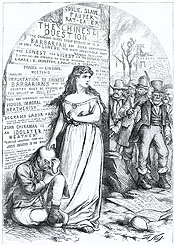

The subject of "the Chinaman" was timely. Large numbers of Chinese immigrants first came to California in the 1850s to work in the mines. In the late 1860s they were 90% of the workforce building the Union Pacific Railroad. By 1871 there were violent "anti-Chinese" riots by native born workers in western cities; that is the occasion for cartoonist Thomas Nast's protest (left). According to the 1880 census, they were still only a small fraction (.002%) of the U.S. population, and almost entirely located in the West,* but even so "Chinese labor" had increasingly become a cause of social anxiety and unrest -- or, as one of the characters of Ah Sin puts it, an "unsolvable political problem." In the curtain speech he made at its New York premiere, MT claimed that the play was "didactic": "The whole purpose of the piece is to afford an opportunity for the illustration of this character. The Chinaman is going to become a frequent spectacle all over America by and by, and a difficult political problem, too. Therefore, it seems well enough to let the public study him a little on the stage beforehand." On 13 August 1877, even as Ah Sin was playing on the New York stage, the California state Senate proposed a very specific "solution" to the problem in An Address to the People of the United States Upon the Evils of Chinese Immigration: after calling the Chinese "morally, the most debased people on the face of the earth," whose "touch is pollution," they insisted that (in still more italics) "justice to our own race demands that they should not be allowed to settle on our soil." When Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, banning all immigration from China, this became the law of the land.

The subject of "the Chinaman" was timely. Large numbers of Chinese immigrants first came to California in the 1850s to work in the mines. In the late 1860s they were 90% of the workforce building the Union Pacific Railroad. By 1871 there were violent "anti-Chinese" riots by native born workers in western cities; that is the occasion for cartoonist Thomas Nast's protest (left). According to the 1880 census, they were still only a small fraction (.002%) of the U.S. population, and almost entirely located in the West,* but even so "Chinese labor" had increasingly become a cause of social anxiety and unrest -- or, as one of the characters of Ah Sin puts it, an "unsolvable political problem." In the curtain speech he made at its New York premiere, MT claimed that the play was "didactic": "The whole purpose of the piece is to afford an opportunity for the illustration of this character. The Chinaman is going to become a frequent spectacle all over America by and by, and a difficult political problem, too. Therefore, it seems well enough to let the public study him a little on the stage beforehand." On 13 August 1877, even as Ah Sin was playing on the New York stage, the California state Senate proposed a very specific "solution" to the problem in An Address to the People of the United States Upon the Evils of Chinese Immigration: after calling the Chinese "morally, the most debased people on the face of the earth," whose "touch is pollution," they insisted that (in still more italics) "justice to our own race demands that they should not be allowed to settle on our soil." When Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, banning all immigration from China, this became the law of the land.

| |

Today, for very good reasons, the term "Chinaman" is seen as offensive, and the Exclusion Act (which was not fully overturned until the 1960s) as one of the most shameful parts of America's historical record. It is much harder to decide how to judge MT and Harte's play as an "illustration" of the character of the Chinese immigrant. In earlier writings about the Chinese in America both writers had vigorously attacked acts of discrimination and violence against them, and Harte had explicitly gone on record to disparage the stereotype of "the Chinaman" that ideologically sanctioned such injustices. Although Americans seem to have overlooked its ironic structure, "Plain Language from Truthful James" satirizes white racial prejudices. In the play, the animosity against Ah Sin, though expressed by both upper and lower class whites, is depicted as mindless, and when the miners threaten at the end of Act 2 to hang "John" -- the culture's generic label for someone like Ah Sin -- there's no doubt how racist their behavior is. At the same time, the tableau with which the scene ends, showing Ah Sin brandishing his laundryman's flatirons in self defense while "shreiking and gibbering Chinese," clearly portrays him as a comic stereotype rather than a sympathetic human being. Today, for very good reasons, the term "Chinaman" is seen as offensive, and the Exclusion Act (which was not fully overturned until the 1960s) as one of the most shameful parts of America's historical record. It is much harder to decide how to judge MT and Harte's play as an "illustration" of the character of the Chinese immigrant. In earlier writings about the Chinese in America both writers had vigorously attacked acts of discrimination and violence against them, and Harte had explicitly gone on record to disparage the stereotype of "the Chinaman" that ideologically sanctioned such injustices. Although Americans seem to have overlooked its ironic structure, "Plain Language from Truthful James" satirizes white racial prejudices. In the play, the animosity against Ah Sin, though expressed by both upper and lower class whites, is depicted as mindless, and when the miners threaten at the end of Act 2 to hang "John" -- the culture's generic label for someone like Ah Sin -- there's no doubt how racist their behavior is. At the same time, the tableau with which the scene ends, showing Ah Sin brandishing his laundryman's flatirons in self defense while "shreiking and gibbering Chinese," clearly portrays him as a comic stereotype rather than a sympathetic human being.According to Margaret Duckett, whose study of MT and Bret Harte remains the fullest scholarly account of their collaboration, it was MT rather than Harte who should be held responsible for the most stereotypical elements in Ah Sin's role. MT always saw Harte more as a rival than a friend, or even a collaborator; in another March 1871 letter about Harte's fame, MT said "I must & will keep shady & quiet till Bret Harte simmers down a little & then I mean to go up head again & stay there." When the partnership between the two men broke down before the script was completed, MT took sole charge of producing it in Washington, D.C., in May, 1877, and then revising it for its Broadway opening at the end of July. The Barrett Collection includes a 15-page manuscript in MT's hand expanding a dialogue in Act 1 that was probably written as part of that revision process; Ah Sin appears in it only briefly, but even in this cameo his dialect and petty thievery are signs of a caricature rather than a character. |

|

In his curtain speech, MT said that "Whoever sees Mr. Parsloe in this piece sees as good and natural and consistent a Chinaman as he could see in San Francisco." Two New York reviewers -- "TRINCULO" in the Spirit of the Times and "NYM CRINKLE" in the Sun, who may have compared notes with each other, or may even be the same man -- rejected this claim. To them Ah Sin is the type of "Chinaman" who could be seen on the minstrel stage, not in San Francisco. The rest of the reviewers, however, praised C. T. Parsloe's "imitation of the Chinaman" as "perfect," "faultless," "a wonderfully photographic portrait of the yellow heathen."

One of the things we can't know is exactly how Parsloe (left) embodied and performed the idea that is suggested by the script. On the other hand, the evidence clearly indicates that Parsloe's "Chinaman" matched the image already in the eastern audiences' minds. The play Ah Sin soon closed -- after a month in New York it launched a national tour that got only as far as St. Louis and a few upstate New York cities before folding -- but Parsloe himself went on in other plays to establish himself as a "yellowface" star, the country's definitive stage "Chinaman." MT's script regularly has Ah Sin gibbering "Chinese" while stealing everything that isn't nailed down and hiding the loot inside his capacious sleeves. Did Parsloe's performance exaggerate or soften these elements of racial caricature? Did his acting turn Ah Sin into a "yellowface" minstrel show or allow audience's to see a human face on the exotic racial Other? In his curtain speech, MT said that "Whoever sees Mr. Parsloe in this piece sees as good and natural and consistent a Chinaman as he could see in San Francisco." Two New York reviewers -- "TRINCULO" in the Spirit of the Times and "NYM CRINKLE" in the Sun, who may have compared notes with each other, or may even be the same man -- rejected this claim. To them Ah Sin is the type of "Chinaman" who could be seen on the minstrel stage, not in San Francisco. The rest of the reviewers, however, praised C. T. Parsloe's "imitation of the Chinaman" as "perfect," "faultless," "a wonderfully photographic portrait of the yellow heathen."

One of the things we can't know is exactly how Parsloe (left) embodied and performed the idea that is suggested by the script. On the other hand, the evidence clearly indicates that Parsloe's "Chinaman" matched the image already in the eastern audiences' minds. The play Ah Sin soon closed -- after a month in New York it launched a national tour that got only as far as St. Louis and a few upstate New York cities before folding -- but Parsloe himself went on in other plays to establish himself as a "yellowface" star, the country's definitive stage "Chinaman." MT's script regularly has Ah Sin gibbering "Chinese" while stealing everything that isn't nailed down and hiding the loot inside his capacious sleeves. Did Parsloe's performance exaggerate or soften these elements of racial caricature? Did his acting turn Ah Sin into a "yellowface" minstrel show or allow audience's to see a human face on the exotic racial Other?Although there was a surprising amount of interest in the play's staging of a game of poker, the reviewers agreed its biggest drawing card was Parsloe's Ah Sin as an ethnic representation. The question remains: what or who was represented? Readers who want to see the play as relatively enlightened might note how its last line, shouted after Ah Sin exposes the villain and resurrects the "murdered" Plunkett by all the miners who have previously abused him, is "Hurrah for Ah Sin." It could be argued that the play's tiresome business of mixing up the identities of the Plunkett and Tempest women might provoke audiences to think about the unreality of all conventions, theatrical or racial, or to wonder who "John Chinaman" really is -- and whether in fact he is different from the "Mellican" (i.e. white) characters. On the other hand, readers who feel the play transforms a Chinese man into the racially stereotypical "Chinaman" might note what the depiction of the jury in the play's concluding trial scene reveals about both MT's scorn for public opinion and his respect for the ease with which prejudices can be manipulated, and conclude that in his anxiety to make the play popular he chose to give his jury, the audiences in the theater, a way to laugh off the unsettling political and moral "problem" of the Chinese immigrant. These are finally questions that Ah Sin's modern readers will have to answer for themselves. |

|

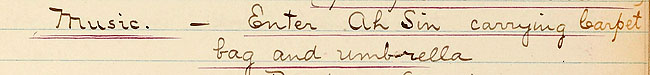

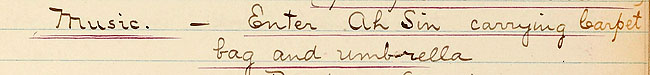

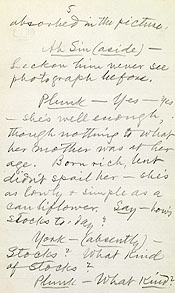

Except for those fifteen pages in MT's hand, no manuscript of Ah Sin survives. The Barrett Collection also contains the only text we have: an undated promptbook written and revised for one of the play's productions. Comparing this script to plot synopses from Washington and New York reviews suggests it is the version MT re-worked in June or July to answer its first reviewers' complaints about certain scenes and overall length, with additions that mainly enlarge Ah Sin's share of the dialogue and stage business. These additions, in the same handwriting as the rest of the script, were made on the otherwise blank lefthand pages of the ledger that was used for the promptbook (for an example, CLICK HERE). You can see additional scans of such pages -- eight altogether -- in each of the play's four acts. In our version of the script, all such "lefthand" additions have been incorporated into the text in bold. Except for those fifteen pages in MT's hand, no manuscript of Ah Sin survives. The Barrett Collection also contains the only text we have: an undated promptbook written and revised for one of the play's productions. Comparing this script to plot synopses from Washington and New York reviews suggests it is the version MT re-worked in June or July to answer its first reviewers' complaints about certain scenes and overall length, with additions that mainly enlarge Ah Sin's share of the dialogue and stage business. These additions, in the same handwriting as the rest of the script, were made on the otherwise blank lefthand pages of the ledger that was used for the promptbook (for an example, CLICK HERE). You can see additional scans of such pages -- eight altogether -- in each of the play's four acts. In our version of the script, all such "lefthand" additions have been incorporated into the text in bold.The script here is intended to be readable, rather than scrupulously scholarly, and so I made several kinds of changes. Smoothly fitting in the "leftpage" additions sometimes made it necessary to omit a few words or phrases from the "rightpage" text. You can see examples of this when you look at the scans, where you'll also see how idiosyncratic and irregular are the amanuensis' Capitalization Practices and habits of punctuation. I've gotten rid of most of the Capital Letters, and added several dozen commas, periods and dashes for clarity. Most stage directions were underlined in purple pencil, and lots of words in the dialogue were underlined in ink; here the stage directions are simply underlined, and the underlined words in speeches are displayed in italics. As I say, there is a lot the script can't tell us (including what kind of "Music" was used to set the scenes and to punctuate major moments in the drama), but this is probably very close to what audiences at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in August, 1877, saw. |

|

|

Because of the fame of the play's two authors, and perhaps also because of concern about the "Chinese problem," reviews of Ah Sin's performance in Washington and New York as well as the transcript of MT's speech on opening night at the Fifth Avenue Theatre were reprinted in papers around the country. Here's a sampling of that coverage, intended to provide another means of access to what the play might have said, not just to the few theater-goers who actually witnessed it during its short life on stage in 1877, but also to larger culture of the times.

|