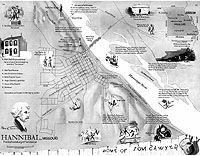

| [In this article, Jerry Allen, author of a biography of MT published in 1954, describes a visit she makes to Hannibal. As you can tell from the excerpts below, she steps right from the anachronistic railroad train into land out of time -- the indulgently remembered time of Tom Sawyer. The article is illustrated with 17 photographs, but nearly all of them are dominated by children, and in 8 of them, including the 2 here, the children look like they got dressed in 1856, not 1956. The article contains only one reference to slavery; it's repeated in the caption to the photo below left. In Allen's article (unlike the remembered worlds of Huck Finn and Pudd'nhead Wilson), not even the thought of slaves being sold down the river disrupts the nostalgic reverie. After the excerpts you can see the way "The St. Petersburg of Tom Sawyer" looks on the map Allen mentions in the essay -- perhaps the only time in its history The National Geographic mapped a semi-imaginary realm.] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

MARK TWAIN remembered it some seventy years ago as a "white town drowsing in the sunshine of a summer's morning." Last year Hannibal, Missouri, tucked away in the heart of the country, attracted more American travelers than Hawaii, a fourth as many as Europe. The high roads and the back roads brought 127,000 visitors. . . . Cupped on the shore of the often-flooding Mississippi, Hannibal lies in a valley edged by 225-foot-high Lovers' Leap (map, page 125). It has neither beaches nor night-clubs--and teen-agers are subject to a 10 o'clock curfew. Crowds come by the busload and in streams of family cars, not for the town's majestic scenery, its climate or resort life, but because here, little changed by time, are the haunts of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. Children, and the parents who tag along with them, have made it one of the most popular home towns in the United States. . . . Injun Joe died in the town of his fame some years ago, an aged and wrinkled half-breed Indian. Yet the awesome fables about him continue hardy and spiked with menace, as a comment I overheard one day on Cardiff Hill shows. "This is the place where Indian Bill murdered the widow," a schoolgirl, garbling her facts a little, told her parents. It was a clear day, a soft time of year, and the locust blooms were fragrant on the hill. But the mother looked warily around for "Indian Bill" and uneasily herded her family from the treacherous ground of fiction. Guides at the cave invariably point to a spot near the entrance where "Injun Joe died just where you're standing." And, invariably, adult visitors and children alike step hastily away. . . . A giant bronze statue of the writer in his later years stands in Hannibal's Riverview Park, overlooking the Mississippi from a height of 200 feet. The work of Frederick Hibbard, it was the 1913 gift of the State of Missouri and bears the inscription: "His religion was humanity and a whole world mourned for him when he died." Riverview Park of some 250 acres is also a gift to the town. A woodland Mark Twain knew as a boy, it was presented by the W. B. Pettibone family and is maintained by them. . . . Like other sights connected with Mark Twain's life in Hannibal, with the single exception of the cave, it is open to everyone without charge. Hannibal has not attempted to profit from his fame. The town owns many of its historic buildings and maintains them at taxpayers' cost. . . . In every country where Mark Twain is read--a circle of books that stretches around the globe--Hannibal is known in its dress of fiction under the many names its author gave it. Yet it was just a village on the Mississippi like many others until Mark Twain made it known as a paradise for boys. Today it is that still. |

|

|

|