Pudd'nhead's Sources

As MT admits in his headnote to The Comedy

of Those Extraordinary Twins, writing The Tragedy of

Pudd'nhead Wilson gave him "a sufficiently hard time."

According to his account, the idea for the story occurred

to him when he saw a picture advertising the exhibition of

the Tocci Twins. This was probably in late 1891. Apparently

MT never saw the Tocci's in person, but he had been

fascinated with the figure of the "Siamese twin" all

through his career (see Twain &

Twins). The image of the Tocci's prompted MT to begin a

farce, based on a conflict between two incompatible selves

forced to inhabit one body. Most of this farce was

published in Those Extraordinary

Twins.

As MT admits in his headnote to The Comedy

of Those Extraordinary Twins, writing The Tragedy of

Pudd'nhead Wilson gave him "a sufficiently hard time."

According to his account, the idea for the story occurred

to him when he saw a picture advertising the exhibition of

the Tocci Twins. This was probably in late 1891. Apparently

MT never saw the Tocci's in person, but he had been

fascinated with the figure of the "Siamese twin" all

through his career (see Twain &

Twins). The image of the Tocci's prompted MT to begin a

farce, based on a conflict between two incompatible selves

forced to inhabit one body. Most of this farce was

published in Those Extraordinary

Twins. MT worked on this

humorous tale during 1892, but as he was writing it (to

quote again from his introductory remarks about Those

Extraordinary Twins), "it changed itself from a farce

to a tragedy" when two characters he had introduced into

the story, "a stranger named Pudd'nhead Wilson, and a woman

named Roxanna," "intruded" themselves into the narrative

and "pushed up into prominence a young fellow named Tom

Driscoll." Tom had been in the tale originally as a rival

to the fair-haired "twin," Angelo, for the affections of

Rowena, whom MT calls "the light-weight heroine." In his

new story, however, Tom became the son of Roxy, "a negro

and a slave" passing as white. The manuscript survives (at

the Morgan Library), but it doesn't clearly answer the

question of why MT's intentions and the mood of his tale

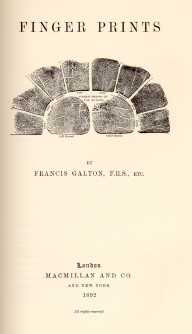

changed. In November, 1892, after he had already decided to

feature the story of changelings but while the details of

that plot were still evolving, MT acquired a copy of

Finger Prints, by

Francis Galton. Galton (1822-1911) was a British scientist

and a cousin of Charles Darwin whose main interest was in

heredity. He coined the term "eugenics." At several points

in Finger Prints he discusses his subject in the

context of race and class, although he acknowledges that

the data will not support his "great expectations" -- that

fingerprints would display racial differences. After

reading Galton's book, MT enthusiastically decided to

feature fingerprints in the story. In Chapter Two MT's

narrator says Roxy's race is "a fiction of law and custom."

When Wilson uses fingerprint evidence in the courtroom to

prove Tom and Chambers' "true" identities, however, he is

in a sense using them to establish race.

MT worked on this

humorous tale during 1892, but as he was writing it (to

quote again from his introductory remarks about Those

Extraordinary Twins), "it changed itself from a farce

to a tragedy" when two characters he had introduced into

the story, "a stranger named Pudd'nhead Wilson, and a woman

named Roxanna," "intruded" themselves into the narrative

and "pushed up into prominence a young fellow named Tom

Driscoll." Tom had been in the tale originally as a rival

to the fair-haired "twin," Angelo, for the affections of

Rowena, whom MT calls "the light-weight heroine." In his

new story, however, Tom became the son of Roxy, "a negro

and a slave" passing as white. The manuscript survives (at

the Morgan Library), but it doesn't clearly answer the

question of why MT's intentions and the mood of his tale

changed. In November, 1892, after he had already decided to

feature the story of changelings but while the details of

that plot were still evolving, MT acquired a copy of

Finger Prints, by

Francis Galton. Galton (1822-1911) was a British scientist

and a cousin of Charles Darwin whose main interest was in

heredity. He coined the term "eugenics." At several points

in Finger Prints he discusses his subject in the

context of race and class, although he acknowledges that

the data will not support his "great expectations" -- that

fingerprints would display racial differences. After

reading Galton's book, MT enthusiastically decided to

feature fingerprints in the story. In Chapter Two MT's

narrator says Roxy's race is "a fiction of law and custom."

When Wilson uses fingerprint evidence in the courtroom to

prove Tom and Chambers' "true" identities, however, he is

in a sense using them to establish race.

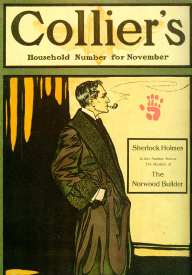

MT's decision to feature fingerprints was either a

cause or an effect of the way his story was becoming a kind

of detective story. In the early summer, 1893, he made the

wholesale manuscript revision he referred to as a "literary

Caesarian operation," pulling out the story of the

"Siamese" twins to "center" the entire narrative, as he put

it in a letter, "on the murder and the trial." In this, the

published version, Pudd'nhead Wilson plays the part of the

analytical observer who will interpret the evidence and, at

the end, solve the mystery and expose the criminal. Like

twins, detectives were a longtime fascination of MT's. One

even appears, briefly and ineptly, in Tom Sawyer

(1875). Most of his variations on the theme of detection

are burlesques or satires, intended to expose the genre

itself. In A Double-Barreled Detective Story (1902),

for example, he brings Sherlock Holmes to the American west

and has him conspicuously fail to solve a murder. Arthur

Conan Doyle's tales about Holmes began appearing in 1887,

with A Study in Scarlet ("The Norwood Builder,"

left, appeared in 1903). By the time MT wrote Pudd'nhead

Wilson, Doyle's stories were extraordinarily popular

with readers around the world. The design of those tales

and the character of Holmes were clearly influences on the

novel as MT wound up writing it, but it is perhaps an open

question whether Pudd'nhead Wilson imitates or

subtly subverts the conventions of detective fiction.

Wilson's "detection" of the murderer restores the social

order that had been violated by both Roxy's switch of the

babies and Tom's murder of Judge Driscoll, but the ante

bellum society he restores is based on slavery.

MT's decision to feature fingerprints was either a

cause or an effect of the way his story was becoming a kind

of detective story. In the early summer, 1893, he made the

wholesale manuscript revision he referred to as a "literary

Caesarian operation," pulling out the story of the

"Siamese" twins to "center" the entire narrative, as he put

it in a letter, "on the murder and the trial." In this, the

published version, Pudd'nhead Wilson plays the part of the

analytical observer who will interpret the evidence and, at

the end, solve the mystery and expose the criminal. Like

twins, detectives were a longtime fascination of MT's. One

even appears, briefly and ineptly, in Tom Sawyer

(1875). Most of his variations on the theme of detection

are burlesques or satires, intended to expose the genre

itself. In A Double-Barreled Detective Story (1902),

for example, he brings Sherlock Holmes to the American west

and has him conspicuously fail to solve a murder. Arthur

Conan Doyle's tales about Holmes began appearing in 1887,

with A Study in Scarlet ("The Norwood Builder,"

left, appeared in 1903). By the time MT wrote Pudd'nhead

Wilson, Doyle's stories were extraordinarily popular

with readers around the world. The design of those tales

and the character of Holmes were clearly influences on the

novel as MT wound up writing it, but it is perhaps an open

question whether Pudd'nhead Wilson imitates or

subtly subverts the conventions of detective fiction.

Wilson's "detection" of the murderer restores the social

order that had been violated by both Roxy's switch of the

babies and Tom's murder of Judge Driscoll, but the ante

bellum society he restores is based on slavery.

Pudd'nhead

Wilson is MT's most direct and

sustained imaginative engagement with the issues of slavery

and race, but although it has never been controversial in

the way Huck Finn is, there is no critical consensus

about whether the novel is racist or anti-racist, about

what the novel is saying or implying about race. Like Huck,

the characters in the book are all shaped by a slaveholding

culture, and so racist themselves. After living in Dawson's

Landing for fifteen years, for example, Wilson thinks of

the "drop of black blood" in Roxy's veins as

"superstitious," and Roxy herself, though a "negro," has so

completely internalized the society's prejudice against her

that she blames her own son's baseness on the "one part

nigger" in him. The idea that there was such a thing as

"black blood" and that a drop of it could determine

character was even more prevalent in the 1890s, when MT was

writing, than in the ante bellum society he is writing

about. The Jim Crow laws being enacted across the South

were given a pseudo-scientific authority by the idea that

race was hereditary, and that racial inferiority or

degradation could be empirically established. Phrases like

"black blood" and "part nigger" would, for its original

readers, link the novel to such contemporary discourse. As

an example of that, I'm including here excerpts from

an essay by Dr. Paul Barringer,

of the University of Virginia hospital, which defines the

"negro" and the threat he represents to civilization in

these quasi-Darwinian terms. In most of his writings, MT

emphasizes the way cultural conditioning (what he calls

training) determines identity and destiny. Pudd'nhead

Wilson says, for example, that Tom "was a bad baby, from the very beginning of his

usurpation" -- which could be interpreted to mean that his

"badness" reflects his nurturing, not his nature. But

Pudd'nhead Wilson also refers to his "native

viciousness," a phrase that echoes the "scientific" racism

of the times. In the manuscript of Pudd'nhead Wilson

MT wrote a passage depicting Tom's own

anguished thoughts about his divided racial

inheritance, in which he specifically asserts that both

"white" and "nigger blood" can be a source of high

qualities, and specifically attributes his own viciousness

to slavery, not innate savagery. But MT deleted the

passage. Whether the published novel was calculated to

challenge or reinforce contemporary doctrines like

Barringer's is a difficult question to decide. If you look

at the reviews included in this site, it's interesting to

note that the first two, written on the basis of the early

chapters as the story appeared serially in The Century

Magazine -- one northern and

favorable, the other southern

and unfavorable -- both clearly assume that by telling

the story of the changelings MT will vindicate the "slave"

Tom in much the same way that, with the switch that occurs

in The Prince and the Pauper, he affirmed the

democratic worth of the "pauper" Tom Canty. The reviews

that were written after the whole novel appeared, however,

don't treat race or slavery as an

important feature of the story. One British review calls the story a

"vigorous indictment of the old social order of the South." On the other hand, the only two American

reviewers who notice the racial theme -- in the Washington Public Opinion and in

the Hartford Times -- have no doubt that it confirms the hereditary effects of "white blood" and "nigger blood." The 1890s were one of the

lowest points in the whole unhappy history of race

relations in America: there were more lynchings than at any

time before or since, and in the Supreme Court's Plessy

v Ferguson decision, the idea that any "black" ancestor

meant you could be labeled "black" and segregated away from

"whites" was upheld as the law of the land of the free.

Whether and how Pudd'nhead Wilson reflects and

participates in these patterns is something modern readers

have to decide for themselves.

Pudd'nhead

Wilson is MT's most direct and

sustained imaginative engagement with the issues of slavery

and race, but although it has never been controversial in

the way Huck Finn is, there is no critical consensus

about whether the novel is racist or anti-racist, about

what the novel is saying or implying about race. Like Huck,

the characters in the book are all shaped by a slaveholding

culture, and so racist themselves. After living in Dawson's

Landing for fifteen years, for example, Wilson thinks of

the "drop of black blood" in Roxy's veins as

"superstitious," and Roxy herself, though a "negro," has so

completely internalized the society's prejudice against her

that she blames her own son's baseness on the "one part

nigger" in him. The idea that there was such a thing as

"black blood" and that a drop of it could determine

character was even more prevalent in the 1890s, when MT was

writing, than in the ante bellum society he is writing

about. The Jim Crow laws being enacted across the South

were given a pseudo-scientific authority by the idea that

race was hereditary, and that racial inferiority or

degradation could be empirically established. Phrases like

"black blood" and "part nigger" would, for its original

readers, link the novel to such contemporary discourse. As

an example of that, I'm including here excerpts from

an essay by Dr. Paul Barringer,

of the University of Virginia hospital, which defines the

"negro" and the threat he represents to civilization in

these quasi-Darwinian terms. In most of his writings, MT

emphasizes the way cultural conditioning (what he calls

training) determines identity and destiny. Pudd'nhead

Wilson says, for example, that Tom "was a bad baby, from the very beginning of his

usurpation" -- which could be interpreted to mean that his

"badness" reflects his nurturing, not his nature. But

Pudd'nhead Wilson also refers to his "native

viciousness," a phrase that echoes the "scientific" racism

of the times. In the manuscript of Pudd'nhead Wilson

MT wrote a passage depicting Tom's own

anguished thoughts about his divided racial

inheritance, in which he specifically asserts that both

"white" and "nigger blood" can be a source of high

qualities, and specifically attributes his own viciousness

to slavery, not innate savagery. But MT deleted the

passage. Whether the published novel was calculated to

challenge or reinforce contemporary doctrines like

Barringer's is a difficult question to decide. If you look

at the reviews included in this site, it's interesting to

note that the first two, written on the basis of the early

chapters as the story appeared serially in The Century

Magazine -- one northern and

favorable, the other southern

and unfavorable -- both clearly assume that by telling

the story of the changelings MT will vindicate the "slave"

Tom in much the same way that, with the switch that occurs

in The Prince and the Pauper, he affirmed the

democratic worth of the "pauper" Tom Canty. The reviews

that were written after the whole novel appeared, however,

don't treat race or slavery as an

important feature of the story. One British review calls the story a

"vigorous indictment of the old social order of the South." On the other hand, the only two American

reviewers who notice the racial theme -- in the Washington Public Opinion and in

the Hartford Times -- have no doubt that it confirms the hereditary effects of "white blood" and "nigger blood." The 1890s were one of the

lowest points in the whole unhappy history of race

relations in America: there were more lynchings than at any

time before or since, and in the Supreme Court's Plessy

v Ferguson decision, the idea that any "black" ancestor

meant you could be labeled "black" and segregated away from

"whites" was upheld as the law of the land of the free.

Whether and how Pudd'nhead Wilson reflects and

participates in these patterns is something modern readers

have to decide for themselves.

Chronologically the earliest source for MT's story

was the world Sam Clemens had grown up in. He'd written

about Hannibal before, notably in Tom Sawyer. As St.

Petersburg Hannibal is called a "western" and a

"southwestern" village; about the only hint in Tom

Sawyer of the social themes that preoccupy

Pudd'nhead Wilson -- slavery, race, miscegenation --

is the reference to the "white, mulatto and negro boys and

girls" Tom could have found hanging around the town pump,

if Aunt Sally hadn't made him whitewash the fence. Aunts

and children played a large role in the farce MT began

with, the comedy of the twins, but in the story he wound up

writing, the tragedy of the changleings, they are pushed to

the margins of the narrative. Probably after the farce

started to darken, MT decided to move the village down the

river, "half a day's journey, per steamboat, below St.

Louis." Along with the move south, the racial issues that

had been marginalized in Tom Sawyer come to occupy

the center of the story. Pudd'nhead Wilson is MT's

most explicit look at Hannibal as a "slaveholding town."

Dawson's Landing is Hannibal, re-viewed -- St. Petersburg

re-imagined without a hint of

nostalgia.

Chronologically the earliest source for MT's story

was the world Sam Clemens had grown up in. He'd written

about Hannibal before, notably in Tom Sawyer. As St.

Petersburg Hannibal is called a "western" and a

"southwestern" village; about the only hint in Tom

Sawyer of the social themes that preoccupy

Pudd'nhead Wilson -- slavery, race, miscegenation --

is the reference to the "white, mulatto and negro boys and

girls" Tom could have found hanging around the town pump,

if Aunt Sally hadn't made him whitewash the fence. Aunts

and children played a large role in the farce MT began

with, the comedy of the twins, but in the story he wound up

writing, the tragedy of the changleings, they are pushed to

the margins of the narrative. Probably after the farce

started to darken, MT decided to move the village down the

river, "half a day's journey, per steamboat, below St.

Louis." Along with the move south, the racial issues that

had been marginalized in Tom Sawyer come to occupy

the center of the story. Pudd'nhead Wilson is MT's

most explicit look at Hannibal as a "slaveholding town."

Dawson's Landing is Hannibal, re-viewed -- St. Petersburg

re-imagined without a hint of

nostalgia.

To the extent that Pudd'nhead Wilson is the

story of Wilson himself, and his rise to the status of

celebrity in Dawson's Landing, I believe that another

significant source was MT himself -- that is, Samuel

Clemens' adult career as "Mark Twain." The story of how

David Wilson went west "to seek his fortune," and fought,

as the last chapter puts it, "against hard luck and

prejudice" in order to become "a made man" is in essence

the archetypal American success story. Its emphases,

however, are particularly Twainian, especially in the way

Wilson's quest is not for money or power, but for attention

and popularity. He becomes a successful lawyer and Mayor of

the village, but the climax of his story is his spectacular

performance in the courtroom, one of the most elaborate and

dramatic of the many performance scenes in MT's fiction.

His achievement is described in the last chapter, when

troops of citizens flock to him and require a speech. This

was not only one of MT's specialties; it also echoes the

happy ending at the end of Tom Sawyer, where

everything Tom says has become remarkable. If Wilson's

triumphant performance in the courtroom, however, is an

imagintive reenactment of MT's popular reception, it makes

MT's decision to call the novel The Tragedy of

Pudd'nhead Wilson that much more resonant.

To the extent that Pudd'nhead Wilson is the

story of Wilson himself, and his rise to the status of

celebrity in Dawson's Landing, I believe that another

significant source was MT himself -- that is, Samuel

Clemens' adult career as "Mark Twain." The story of how

David Wilson went west "to seek his fortune," and fought,

as the last chapter puts it, "against hard luck and

prejudice" in order to become "a made man" is in essence

the archetypal American success story. Its emphases,

however, are particularly Twainian, especially in the way

Wilson's quest is not for money or power, but for attention

and popularity. He becomes a successful lawyer and Mayor of

the village, but the climax of his story is his spectacular

performance in the courtroom, one of the most elaborate and

dramatic of the many performance scenes in MT's fiction.

His achievement is described in the last chapter, when

troops of citizens flock to him and require a speech. This

was not only one of MT's specialties; it also echoes the

happy ending at the end of Tom Sawyer, where

everything Tom says has become remarkable. If Wilson's

triumphant performance in the courtroom, however, is an

imagintive reenactment of MT's popular reception, it makes

MT's decision to call the novel The Tragedy of

Pudd'nhead Wilson that much more resonant.