Connecticut Yankee was shorter than

a subscription book was supposed to be, so its design took

full advantage of Beard's pictures (and a generous amount of

white space) to stretch its length. Although he had to work

quickly to keep the book on deadline (according to Beard, the

illustrations were produced in about 70 days), Beard's work

displays a lot of wit, elegance and attention to both visual

and thematic detail. One of the striking characteristics is

the way the drawings feature many well-known 19th-century

faces on the book's 6th-century characters. Beard's usual

practice as an illustrator was to work from both live models

and "a large collection of photographs" of contemporary

celebrities and "prominent people." All MT's readers would

have recognized the original of the sow at left, for example,

though not all would have been amused. Clicking on her will

take you to a gallery displaying

Beard's drawings of famous people as characters in the

novel, and the originals they are based on.

Connecticut Yankee was shorter than

a subscription book was supposed to be, so its design took

full advantage of Beard's pictures (and a generous amount of

white space) to stretch its length. Although he had to work

quickly to keep the book on deadline (according to Beard, the

illustrations were produced in about 70 days), Beard's work

displays a lot of wit, elegance and attention to both visual

and thematic detail. One of the striking characteristics is

the way the drawings feature many well-known 19th-century

faces on the book's 6th-century characters. Beard's usual

practice as an illustrator was to work from both live models

and "a large collection of photographs" of contemporary

celebrities and "prominent people." All MT's readers would

have recognized the original of the sow at left, for example,

though not all would have been amused. Clicking on her will

take you to a gallery displaying

Beard's drawings of famous people as characters in the

novel, and the originals they are based on. MT's original

intention was to supervise Beard's work closely.

Intending as always for the book to be as popular as

possible, he was anxious about the points at which his story

would rub up against contemporary beliefs, and as with

Kemble's work on Huck Finn, he expected the

illustrations to tone the book down: "I have aimed to put all

the crudeness and vulgarity in the book," he wrote Beard,

"and I depend on you for the refinement and scintillating

humor for which you are so famous." But he liked the first

samples Beard submitted so much that he decided to leave the

artist alone to "obey his own inspiration" -- "I want

his genius to be wholly unhampered." MT was delighted with

the results. You can see a gallery of

MT's favorite pictures by clicking here. After the novel

was published, MT wrote an acquaintance that "to my mind the

illustrations are better than the book -- which is a good

deal for me to say, I reckon."

MT's original

intention was to supervise Beard's work closely.

Intending as always for the book to be as popular as

possible, he was anxious about the points at which his story

would rub up against contemporary beliefs, and as with

Kemble's work on Huck Finn, he expected the

illustrations to tone the book down: "I have aimed to put all

the crudeness and vulgarity in the book," he wrote Beard,

"and I depend on you for the refinement and scintillating

humor for which you are so famous." But he liked the first

samples Beard submitted so much that he decided to leave the

artist alone to "obey his own inspiration" -- "I want

his genius to be wholly unhampered." MT was delighted with

the results. You can see a gallery of

MT's favorite pictures by clicking here. After the novel

was published, MT wrote an acquaintance that "to my mind the

illustrations are better than the book -- which is a good

deal for me to say, I reckon." One of the themes MT was

most anxious about was the novel's aggressive attack on

religion: "an established church," Hank writes, "is an

established slave pen." Although Hall told MT that "it was

the Catholic Church that would principally attack [the

novel], and they were not book buyers anyway," it was MT's

design to downplay the book's anti-religious sentiments, to

avoid, for example, including "any religious matter in the

Prospectus" that his book agents would show prospective

customers (see Sales

Prospectus). Beard, however, was a member of the Society

of Friends (the Quakers), and overtly hostile to the

institutionalized Christianity. Many of his drawings rely on

familiar American anti-Catholic stereotypes, as you can see

by clicking on the cleric at

left.

One of the themes MT was

most anxious about was the novel's aggressive attack on

religion: "an established church," Hank writes, "is an

established slave pen." Although Hall told MT that "it was

the Catholic Church that would principally attack [the

novel], and they were not book buyers anyway," it was MT's

design to downplay the book's anti-religious sentiments, to

avoid, for example, including "any religious matter in the

Prospectus" that his book agents would show prospective

customers (see Sales

Prospectus). Beard, however, was a member of the Society

of Friends (the Quakers), and overtly hostile to the

institutionalized Christianity. Many of his drawings rely on

familiar American anti-Catholic stereotypes, as you can see

by clicking on the cleric at

left.

Beard was also a staunch supporter of the "single-tax" political and economic program of contemporary reformer Henry George. His drawings not only enthusiastically reflect the novel's satire on various forms of aristocratic privilege; they also use MT's text as the occasion for giving visual expression to many of the ideas Beard found in George's book, Progress and Property. Click on the burdens at left for some examples of Beard's most explicitly political cartoons.

The artists whose

pictures appeared on every second or third page inevitably

shaped the way contemporary readers "saw" and understood the

first editions of MT's texts. Uncharacteristically, MT was

entirely pleased with Beard's work: "What luck it was to find

you!" he told Beard; "There are a hundred artists who could

illustrate any other book of mine, but there was only one who

could illustrate this one." Yet Beard took large liberties in

his drawings. Many of them don't illustrate anything that

appears in the text, but instead extrapolate from MT's words

various ideas that have to be considered Beard's own thematic

contributions to Connecticut Yankee. Although MT gives

Hank the nickname "Sir Boss," for example, Beard's drawings

often equate the injustices of medieval feudalism with the

patterns of late-nineteenth-century American capitalism. For

some examples of Beard's most

"un-authorized" illustrations, click on the robber baron

at left.

The artists whose

pictures appeared on every second or third page inevitably

shaped the way contemporary readers "saw" and understood the

first editions of MT's texts. Uncharacteristically, MT was

entirely pleased with Beard's work: "What luck it was to find

you!" he told Beard; "There are a hundred artists who could

illustrate any other book of mine, but there was only one who

could illustrate this one." Yet Beard took large liberties in

his drawings. Many of them don't illustrate anything that

appears in the text, but instead extrapolate from MT's words

various ideas that have to be considered Beard's own thematic

contributions to Connecticut Yankee. Although MT gives

Hank the nickname "Sir Boss," for example, Beard's drawings

often equate the injustices of medieval feudalism with the

patterns of late-nineteenth-century American capitalism. For

some examples of Beard's most

"un-authorized" illustrations, click on the robber baron

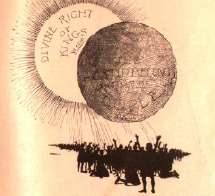

at left. Because MT wanted Connecticut Yankee

to appear in time for the Christmas trade, the sales

prospectus had to be prepared before Beard had finished many

illustrations. Thus the passages from the novel included in

the prospectus are unillustrated. But MT approved Hall's

suggestion to include a 16-page

"signature" of illustrations at the end of the

prospectus. Hall promised MT the sampling did not include

pictures of "anything that would apply directly to the church

or that is strongly political, but whatever makes fun of

royalty and nobility . . . we have put in, as that will suit

the American public well." Hall himself, as "a help to agents

in selling the book," wrote interpretive captions for each

illustration, describing "whatever the picture is intended to

represent." To see what pictures were selected, and how they

were explained to MT's audience, click on the eclipse at

left.

Because MT wanted Connecticut Yankee

to appear in time for the Christmas trade, the sales

prospectus had to be prepared before Beard had finished many

illustrations. Thus the passages from the novel included in

the prospectus are unillustrated. But MT approved Hall's

suggestion to include a 16-page

"signature" of illustrations at the end of the

prospectus. Hall promised MT the sampling did not include

pictures of "anything that would apply directly to the church

or that is strongly political, but whatever makes fun of

royalty and nobility . . . we have put in, as that will suit

the American public well." Hall himself, as "a help to agents

in selling the book," wrote interpretive captions for each

illustration, describing "whatever the picture is intended to

represent." To see what pictures were selected, and how they

were explained to MT's audience, click on the eclipse at

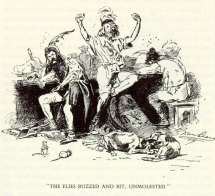

left. Dan Beard

included himself at the Round Table: the figure in the middle

at left is a self-portrait. He and MT wound up becoming

friends, and MT employed him to illustrate a number of other

texts, including The American Claimant, The Million

Dollar Banknote, Tom Sawyer, Abroad and

Following the Equator. Beard himself claimed, however,

that most publishers and editors were reluctant to hire him

after his critiques of Catholicism and capitalism appeared in

Connecticut Yankee. According to him, "the influence

of vested interests" produced what he called a "boycott" --

what we would call a blacklisting -- "for about ten years."

Despite the revelry on display in his self-portrait, Beard

also became the organizer of the American Boy Scouts, and

served as National Scout Commissioner from 1910 until his

death in 1941.

Dan Beard

included himself at the Round Table: the figure in the middle

at left is a self-portrait. He and MT wound up becoming

friends, and MT employed him to illustrate a number of other

texts, including The American Claimant, The Million

Dollar Banknote, Tom Sawyer, Abroad and

Following the Equator. Beard himself claimed, however,

that most publishers and editors were reluctant to hire him

after his critiques of Catholicism and capitalism appeared in

Connecticut Yankee. According to him, "the influence

of vested interests" produced what he called a "boycott" --

what we would call a blacklisting -- "for about ten years."

Despite the revelry on display in his self-portrait, Beard

also became the organizer of the American Boy Scouts, and

served as National Scout Commissioner from 1910 until his

death in 1941.