Feburary 1886

from The Dance in Place Congo

The Place Congo, at the opposite end of the street, was at the opposite end of everything. One was on the highest ground; the other on the lowest. The one was the rendezvous of the rich man, the master, the military officer--of all that went to make up the ruling class; the other of the butcher and baker, the raftsman, the sailor, the quadroon, the painted girl, and the negro slave. No meaner name could be given the spot. The negro was the most despised of human creatures and the Congo the plebian among negroes. The white man's plaza had the army and navy on its right and left, the court-house, the council-hall and the church at its back, and the world before it. The black man's was outside the rear gate, the poisonous wilderness on three sides and the proud man's contumely on its front.

Before the city overgrew its flimsy palisade walls, and closing in about this old stamping-ground gave it set bounds, it was known as Congo Plains. There was wide room for much field sport, and the Indian villagers of the town's outskirts and the lower class of white Creoles made it the ground of their wild game of raquette. Sunday afternoons were the time for it. Hence, beside these diversions there was, notably, another.

The hour was the slave's term of momentary liberty, and his simple, savage, musical and superstitious nature dedicated it to amatory song and dance tinctured with his rude notions of supernatural influences.

There

were other dances. Only a few years ago I was honored with

an invitation, which I had to decline, to see danced the

Babouille, the Cata (or Chacta), the Counjaille, and the

Calinda. Then there were the Voudou, and the Congo, to

describe which would not be pleasant. The latter, called

Congo also in Cayenne, Chica in San Domingo, and in the

Windward Islands confused under one name with the Calinda,

was a kind of Fandango, they say, in which the Madras

kerchief held by its tip-ends played a graceful part.

There

were other dances. Only a few years ago I was honored with

an invitation, which I had to decline, to see danced the

Babouille, the Cata (or Chacta), the Counjaille, and the

Calinda. Then there were the Voudou, and the Congo, to

describe which would not be pleasant. The latter, called

Congo also in Cayenne, Chica in San Domingo, and in the

Windward Islands confused under one name with the Calinda,

was a kind of Fandango, they say, in which the Madras

kerchief held by its tip-ends played a graceful part.

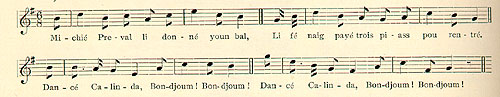

The true Calinda was bad enough. In Louisiana, at least, its song was always a grossly personal satirical ballad, and it was the favorite dance all the way from there to Trinidad. To dance it publicly is not allowed this side the West Indies. All this Congo Square business was suppressed at one time; 1843, says tradition.

The Calinda was a dance of multitude, a sort of vehement cotillion. The contortions of the encircling crowd were strange and terrible, the din was hideous. One Calinda is still familiar to all Creole ears; it has long been a vehicle for the white Creole's satire; for generations the man of municipal politics was fortunate who escaped entirely a lampooning set to its air.

In my childhood I used, at one time, to hear, every

morning, a certain black marchande des

calas--peddler-woman selling rice croquettes--chanting

the song as she moved from street to street at the sunrise

hour with her broad, shallow, laden basket balanced on her

head.

The number of stanzas has never been counted; here are a few of them.

"It was in a stable that they had this gala night," says the song; "the horses there were greatly astonished. Preval was captain; his coachman, Louis, was master of ceremonies. There were negresses made prettier than their mistresses by adornments stolen from the ladies' wardrobes (armoires). But the jailer found it all so funny that he proposed to himself to take an unexpected part; the watchmen came down"--"Dans l'equirie la 'y' avé grand gala;

Mo cré choual la yé t b'en étonné.Miché Preval, li té capitaine bal;

So cocher Louis, té maite cérémonie.Y avé des négresse belle passé maitresse,

Qui volé bel-bel dans l'ormoire momselle.. . . . . .

Ala maite la geole li trouvé si drole,

Li dit, "moin aussi, mo fé bal ici."Ouatchman la yé yé tombé la dans;

Yé fé gran' déga dans léquirie la." etc.

No official exaltation bought immunity from the jeer of the Calinda. Preval was a magistrate. Stephen Mazureau, in his attorney-general's office, the song likened to a bull-frog in a bucket of water. A page might be covered by the roll of victims. The masters winked at these gross but harmless liberties and, as often as any others, added stanzas of their own invention.

The Calinda ended these

dissipations of the summer Sabbath afternoons. They could

not run far into the night, for all the fascinations of all

the dances could not excuse the slave's tarrying in public

places after a certain other bou-djoum! (that was

not of the Calinda, but of the regular nine-o'clock evening

gun) had rolled down Orleans street from the Place d'Armes;

and the black man or woman who wanted to keep a whole skin

on the back had to keep out of the Calaboose. Times have

changed, and there is nothing to be regretted in the change

that has come over Congo Square. Still a glamour hangs over

its dark past. There is the pathos of slavery, the poetry

of the weak oppressed by the strong, and of limbs that

danced after toil, and of barbaric love-making. The rags

and semi-nakedness, the bamboula drum, the dance, and

almost the banjo, are gone; but the bizarre melodies

and dark lovers' apostrophes live on; and among them the

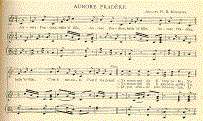

old Counjaille song of Aurore Pradère

The Calinda ended these

dissipations of the summer Sabbath afternoons. They could

not run far into the night, for all the fascinations of all

the dances could not excuse the slave's tarrying in public

places after a certain other bou-djoum! (that was

not of the Calinda, but of the regular nine-o'clock evening

gun) had rolled down Orleans street from the Place d'Armes;

and the black man or woman who wanted to keep a whole skin

on the back had to keep out of the Calaboose. Times have

changed, and there is nothing to be regretted in the change

that has come over Congo Square. Still a glamour hangs over

its dark past. There is the pathos of slavery, the poetry

of the weak oppressed by the strong, and of limbs that

danced after toil, and of barbaric love-making. The rags

and semi-nakedness, the bamboula drum, the dance, and

almost the banjo, are gone; but the bizarre melodies

and dark lovers' apostrophes live on; and among them the

old Counjaille song of Aurore Pradère

| AURORE PRADÉRE. | |

| CHO. | Aurore Pradère, pretty maid,

(ter) She's just what I want and her I'll have. |

| SOLO. | Some folks say she's too pretty, quite; Some folks they say she's not polite; All this they say--Psha-a-ah! More fool am I! For she's what I want and her I'll have. |

| CHO. | Aurore Pradère, pretty maid,

(ter) She's just what I want and her I'll have. |

| SOLO. | Some say she's going to the bad; Some say that her mamma went mad; All this they say--Psha-a-ah! More fool am I! For she's what I want and her I'll have. |

Mr. Ware and his associate compilers have neither of these stanzas, but one very pretty one; the third in the music as printed here, and which we translate as follows:

| SOLO. | A muslin gown she doesn't choose, She doesn't ask for broidered hose, She doesn't want prunella shoes, O she's what I want and her I'll have. |

| CHO. | Aurore Pradère, etc. |

The Century Magazine

April 1886

from Creole Slave Songs

One of the best of these Creole love-songs--one that

the famed Gottschalk, himself a New Orleans Creole of pure

blood, made use of--is the tender lament of one who sees

the girl of his heart's choice the victim of chagrin in

beholding a female rival wearing those vestments of extra

quality that could only be the favors which both women had

coveted from the hand of some one in the proud master-caste

whence alone such favors could come. "Calalou," says the

song, "has an embroidered petticoat, and Lolotte, or Zizi,"

as it is often sung, "has a--heartache." Calalou, here, I

take to be a derisive nickname. Originally it is the term

for a West Indian dish, a noted ragout. It must be intended

to apply here to the quadroon women who swarmed into New

Orleans in 1809 as refugees from Cuba, Guadeloupe, and

other islands where the war against Napoleon exposed them

to Spanish and British aggression. It was with this great

influx of persons neither savage nor enlightened, neither

white nor black, neither slave nor truly free, that the

famous quadroon caste arose and flourished. If Calalou, in

the verse, was one of these quadroon fair ones, the song is its own explanation.

One of the best of these Creole love-songs--one that

the famed Gottschalk, himself a New Orleans Creole of pure

blood, made use of--is the tender lament of one who sees

the girl of his heart's choice the victim of chagrin in

beholding a female rival wearing those vestments of extra

quality that could only be the favors which both women had

coveted from the hand of some one in the proud master-caste

whence alone such favors could come. "Calalou," says the

song, "has an embroidered petticoat, and Lolotte, or Zizi,"

as it is often sung, "has a--heartache." Calalou, here, I

take to be a derisive nickname. Originally it is the term

for a West Indian dish, a noted ragout. It must be intended

to apply here to the quadroon women who swarmed into New

Orleans in 1809 as refugees from Cuba, Guadeloupe, and

other islands where the war against Napoleon exposed them

to Spanish and British aggression. It was with this great

influx of persons neither savage nor enlightened, neither

white nor black, neither slave nor truly free, that the

famous quadroon caste arose and flourished. If Calalou, in

the verse, was one of these quadroon fair ones, the song is its own explanation.

"Poor little Miss Zizi!" is what it

means--"She has pain, pain in her little heart." "À

li" is simply the Creole possessive form; "corps à

moin" would signify simply myself. Calalou is wearing a

Madras turban; she has on an embroidered petticoat; [they

tell their story and] Zizi has achings in her heart. And

the second stanza moralizes: "When you wear the chain of

love"--maybe we can make it rhyme:

"Poor little Miss Zizi!" is what it

means--"She has pain, pain in her little heart." "À

li" is simply the Creole possessive form; "corps à

moin" would signify simply myself. Calalou is wearing a

Madras turban; she has on an embroidered petticoat; [they

tell their story and] Zizi has achings in her heart. And

the second stanza moralizes: "When you wear the chain of

love"--maybe we can make it rhyme:

Bid all happiness good-bye."