[The Post put this review in the lead position on its front page, and included with it these two illustrations.]

Dramatic and Humorous Recitations from "Dr. Sevier"--

Merriment at the Expense of the German Language and

A Thrilling Ghost Story.

"Mark Twain" and George W. Cable alternately appeared on the platform of Congregational Church last night. As soon as one bowed his exit the other ran up the steps, not because they were in a hurry, as the former explained, but because the programme was long.

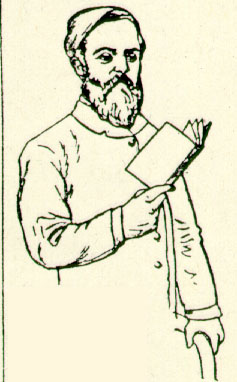

Mr. Cable was the first to appear, and was greeted with applause. He is of medium height, slender, with a jet black silky beard, and his dark eyes sparkle with intelligence. His rich and melodious voice rises to a high falsetto in its portrayal of female character. In his opening selection he impersonated Narcisse, John and Mary Richling. One forgot the speaker and saw John, grave and quiet, and Mary, "pushing her small feet back and forth on the floor," listening to the delightful accent and original philosophy of Narcisse, as he sat twitching uneasily in his chair, with his mind fixed on "that fifty dolla" which he "could baw from Mistoo Itchling." Afterwards it was Kate Reilly, with her smirking and her brogue, who called Ristofalo "a desaving crature," while the stumpy, honest Italian answered, "Dat's alright," and putting his arm around her called her "Kate" to her outward astonishment but inward delight; or, later, the audience followed Mary and little Alice and the spy in their lonely midnight ride through forest roads and across cold streams until they reached the road. How vividly the picture was drawn! and then, when the soldiers sprang up in the road and there was the gleam of carbines and the sound of firing, how one's heart throbbed when the baby cried "Mother," and Mary whispered to it and lashed her horse in the same instant, while the spy heightened the dramatic action by his shout of victory. In his songs, too, Mr. Cable touched the audience, and the weird, beautiful music gained for him hearty applause.

As for "Mark Twain," Father Time has no mercy even upon a professional mirth-provoker and has plentifully sifted his hair and heavy drooping moustache with fine white powder. His face is as clean cut as cameo. He speaks in a sort of mechanical drawl and with a most bored expression of countenance. The aggrieved way in which he gazes with tilted chin over the convulsed faces of his audience, as much as to say, "Why are you laughing?" is irresistible in the extreme. He jerks out a sentence or two and follows it with a silence that is more suggestive than words. His face is immoveable while his hearers laugh, and as he waits for the merriment to subside, his right hand plays with his chin and his left finds its way to the pocket of his pants. Occasionally the corners of his mouth twitch with inward fun, but never is a desire to laugh allowed to get the better of him. These characteristics agree so well with his description of himself in his books -- Innocence victimized by the world, flesh, and Devil -- that one cannot fail to establish the resemblance and laugh at the grotesque image.

"Mark Twain," for it does not seem natural to call him Mr. Clemens, first recited from the advance sheets of "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn." This classic was an account of King Sollymun, his wives, wealth and wisdom. It was down in the Mississippi Valley. Huck Finn, a white boy who was maltreated by the old man, ran away with Nigger Jim from the plantation and camped out in the woods. Their conversation was about kings. Jim wasn't familiar with kings. The only kings he knew anything about were the four kings in a pack of cards. Then Huck told what he knew about kings in general and "Sollymun" in particular. To his youthful mind they were persons who got $1000 per month, went to war occasionally, but "as a general thing they hung around a harem." Jim was disposed to question "Sollymun's" wisdom in cutting the disputed child in two. In vain Huck told him he did not understand the case. "It was all on 'count of his raising," said Jim. "He had about five million children. Take a man with two or three. Is he gwine to be wasteful of children like dat?"

Twain once went to Germany and wrestled with the language of that country. "There is one disease," he told his audience, "which is sure to affect everybody at some time or other during his life, and that is the disease which prompts a man to learn a foreign language." The audience guessed what was coming, and laughed. "I escaped that infection," continued the speaker, in deliberate drollness, "for a long time, the major part of my life, in fact; but I did not escape it entirely. I had learned a smattering of Chinese, one or two Indian dialects and some other kindred classic languages, but nothing serious. The serious part came later. I went to Germany two years ago, with an evil instinct that I could learn the German language. I know better now. [Laughter.] I went to work at it, worked hard and hopefully, fought a good, honest fight with it, but the German language has been in the business longer than I have [laughter] and it came out ahead." Then the audience laughed again, and when the speaker continued to relate his struggles with the nouns and adjectives, and his acquaintance with a dissipated student of Heidelberg, who said he "would rather decline four drinks than one noun," his hearers shook with visible emotion. All this was by way of prelude to the "Tragic Tale of a Fishwife," wherein English words were given the same gender as if they had been German, the result being a comical mixture, absurd in the highest degree.

A ghost story ended the programme. The voice in the whistling wind moaned, "Who's got my golden arm?" and the figure came up the stairs and bent over the stingy husband. "You've got it," it cried, and the audience jumped. That was the finale.

To-night the President will be present.