SAMUEL L. CLEMENS (Mark Twain) I consider one of the greatest geniuses of our time, and as great a philosopher as humorist. I think I know him better than he is known to most men -- wide as his circle of acquaintances is, big as is his reputation. He is as great a man as he is a genius, too. Tenderness and sensitiveness are his two strongest traits. He has one of the best hearts that ever beat. One must know him well fully to discern all of his best traits. He keeps them entrenched, so to speak. I rather imagine that he fights shy of having it generally suspected that he is kind and tenderhearted, but many of his friends do know it. He possesses some of the frontier traits -- a fierce spirit of retaliation and the absolute confidence that life-long "partners," in the Western sense, develop. Injure him, and he is merciless, especially if you betray his confidence. Once a lecture manager in New York, whom he trusted to arrange the details of a lecture in Steinway Hall, swindled him to the amount of $1,500, and afterward confessed it, offering restitution to that amount, but not until the swindle had been discovered. They were on board ship at the time, and "Mark" threatened to throw the fellow overboard, meaning it, too, but he fled ashore. In "The Gilded Age" "Mark " immolated him. (Mr. Griller, Lecture Agent, page 438, London Edition). The fellow died soon afterward, and James Redpath, who was a witness to the scene on the steamboat, and who knew the man well, insisted that "Mark's" arrow killed him; but he would have fired it all the same had he known what the result would be.

General Grant and "Mark Twain" were the greatest of friends. C. L. Webster & Co. (Mark Twain) published "General Grant's Memoirs," yet how like and unlike are the careers of the soldier and the citizen!

Grant: poor, a tanner, small farmer, selling cordwood for a living, with less prospect for rising than any ex-West Pointer in the army; then the greatest military reputation of the age; twice President of the United States; the foremost civilian of the world; the most honored guest of peoples and rulers who ever made the circuit of the earth.

"Mark Twain": a printer's apprentice in a small Missouri River town; then a "tramping jour" printer; a Mississippi roustabout guarding freight piles on the levee all night for pocket money; river pilot; a rebel guerilla; a reporter in a Nevada mining town; then suddenly the most famous author of the age; a man of society, with the most aristocratic clubs of America, and all around the civilized globe, flung open to him; adopted with all the honors into one of the most exclusive societies on this continent, the favored companion of the most cultivated spirits of the age, welcomed abroad in all the courts almost as a crowned head. "Peace hath its victories," etc.

There is indeed another parallel between Grant and Twain, Grant found himself impoverished two years before his death, when was left for him the most heroic part of his lifework, to write his memoirs (while he knew he was dying), for which, through his publishers, C. L. Webster & Co. (Twain), his family received nearly half a million dollars. That firm failed in 1894, leaving liabilities to the amount of $80,000 over and above all it owned for "Mark" to pay, and which he has earned with his voice and pen in a tour around the world, paying every creditor in full, in one year's less time than he calculated when he started at Cleveland on the 15th day of July, 1895. Yes, there is a parallel between the two great heroes in courage and integrity; they are more like than unlike.

"Mark Twain" became a lecturer in California in 1869, after he had returned to San Francisco from the Sandwich Islands. He had written from there a series of picturesque and humorous letters for the Sacramento Union, a California journal, and was asked to lecture about the islands. He tells of his first experience with great glee. He had written the lecture and committed it to memory, and was satisfied with it. Still, he dreaded a failure on the first night, as he had had no experience in addressing audiences. Accordingly, he made an arrangement with a woman friend, whose family was to occupy one of the boxes, to start the applause if he should give the sign by looking in her direction and stroking his moustache. He thought that if he failed to "strike" the audience he would be encouraged by a round of applause, if any one would start it after he had made a good point.

Instead of failure, his lecture was a boundless success. The audience rapturously applauded every point, and "Mark" forgot all about his instructions to the lady. Finally, as he was thinking of some new point that occurred to him as he was talking, without a thought of the lady at all, he unconsciously put his hand up to his moustache, and happened to turn in the direction of the box. He had said nothing just then to cause even his appreciative audience to applaud; but the lady took his action for the signal, and nearly broke her fan in striking it against the edge of the box. The whole house joined her applause.

This unexpected and malapropos applause almost knocked "Mark" off his pins; but he soon recovered himself, and became at once one of the favorites of the platform. He lectured a year or two in the West, and then, by Petroleum V. Nasby's advice, in 1872-73, James Redpath invited him to come East and he made his first appearance in Boston, in the Redpath Lyceum Music Hall. His success was instantaneous, and he has ever since remained the universal platform favorite to this date, not only in America, in Australia, in India, in the Cape Colonies, and throughout Great Britain; but in Austria and in Germany, where large crowds pay higher prices to see and to hear "Mark Twain" than any other private citizen that has ever lived.

In his tour around the world "Mark Twain" earned with his voice and pen money enough to pay all his creditors (Webster & Co., publishers) in full, with interest, and this he did almost a year sooner than he had originally calculated. Such a triumphal tour has never before been made by any American since that memorable tour around the world by General Grant. Samuel L. Clemens has been greeted in France, Switzerland, Germany, and England almost like a crowned head.

He wrote me from Paris, May 1, 1895: "I've a notion to read a few times in America before I sail for Australia. I'm going to think it over and makeup my mind." On May 18th he arrived in this country, and I made arrangements for him to lecture in twenty-one cities on his way to the Pacific, beginning in Cleveland, July 15th, and ending in Vancouver, British Columbia, August 15th. From that place he was to sail for Australia, via Honolulu, where it was planned that he should speak while the ship was waiting; but owing to yellow fever no landing was made there, and over $1,600 was returned to the disappointed people of Honolulu.

June 11th he wrote me from Elmira that if we have a circular for this brief campaign, the chief feature, when speaking of him should be, that he (M. T.) is on his way to Australia and thence around the globe on a reading and talking tour to last twelve months, that travelling around the world is nothing, as everybody does it. But what he was travelling for was unusual; everybody didn't do that.

"I like the approximate itinerary first rate. It is lake all the way from Cleveland to Duluth. I wouldn't switch aside to Milwaukee for $200,000." His original idea was to lecture in nine cities, besides two or three others on the Pacific Coast. I was to have one-fourth of the profits except in San Francisco, where he was to have four-fifths. But we did not go to San Francisco.

There were five of us in the party: Mr. and Mrs. Clemens, Clara (one of their daughters), Mrs. Pond and myself. During the journey I kept a detailed journal, from which I shall quote:

At the Stillman with "Mark Twain," his wife, and their daughter Clara. "Mark" looks badly fatigued.

We have very comfortable quarters here. "Mark" went immediately to bed on our arrival. He is nervous and weak.

Reporters from all the morning and evening papers called and interviewed him. It seemed like old times again, and "Mark" enjoyed it.

The young men called at 3 p.m.. and paid me the fee for the lecture, which took place in Music Hall. There were 4,200 people present, at prices ranging from 25 cents to $1. It was nine o'clock before the crowd could get in and "Mark" begin. As he hobbled upon the stage, there was a grand ovation of cheers and applause, which continued for some time. Then he began to speak, and before he could finish a sentence the applause broke out again. So it went on for over an hour on a mid-July night, with the mercury trying to climb out of the top of the thermometer. "Mark Twain" kept that vast throng in convulsions.

Ninety degrees in the shade at 7:30 a.m. Good notices of "Mark Twain's"lecture appear in all the papers. "Mark" spent all day in bed until five o'clock, while I spent the day in writing to all correspondents ahead. If Sault Ste. Marie, the next engagement, turns out as well in proportion as this place, our tour is a success. "Mark" and family were invited out to dinner with some old friends and companions of the Quaker City tour. He returned very nervous and much distressed. We discover a remarkable woman in Mrs. Clemens. There's a good time in store for us all.

Our party left Cleveland for Mackinac at seven o'clock. "Mark" is feeling very poorly. He is carrying on a big fight against his bodily disability. All that has been said of this fine ocean ship on the Great Lakes is not exaggerated. Across Lake Erie to Detroit River, Lake St. Clair, and the St. Clair River is a most charming trip. "Mark" and Mrs. Clemens are very cheerful to-day. The passengers have discovered who they are, and consequently our party is the centre of attraction. Wherever "Mark" sits or stands on the deck of the steamer, in the smoking room, dining room, or cabin, he is the magnet, and people strain their necks to see him and to catch every word he utters.

On this lake trip occurred an incident of which I have already written. It was the second day out on Lake Huron, and "Mark" was on deck in the morning for the first time. Many people made excuses for speaking to him. One man had stopped off in Cleveland on purpose to hear him. Another, from Washington Territory, who had lived forty years in the West, owned a copy of "Roughing It," which he and his wife knew by heart. One very gentle, elderly lady wished to thank him for the nice things he has written and said of cats. But the one that interested "Mark" the most was a young man who asked him if he had ever seen or used a shaving stone, handing him one. It was a small, peculiar, fine-grained sandstone, the shape of a miniature grindstone, and about the size of an ordinary watch. He explained that all you had to do was to rub your face with it and the rough beard would disappear, leaving a clean, shaven face.

"Mark" took it, rubbed it on his unshaven cheek, and expressed great wonder at the result. He put it in his vest pocket very unceremoniously, remarking at the same time: "The Madam (he generally speaks of Mrs. Clemens as 'The Madam') will have no cause to complain of my never being ready in time for church because it takes so long to shave. I will put this into my vest pocket on Sunday. Then, when I get to church, I'll pull the thing out and enjoy a quiet shave in my pew during the long prayer."

We came by steamer F. S. Faxton, of the Arnold Line. It was an ideal excursion among the islands. Although it was cold, none of our party would leave the deck until the dinner bell rang. "Mark" said: "That sounds like an old-fashioned summons to dinner. It means a good, old-fashioned, unpretentious dinner, too. I'm going to try it." We all sat down to a table the whole length of the cabin. We naturally fell in with the rush, and all got seats. It was a good dinner, too; the best ever I heard of for 25 cents.

We reached the Grand Hotel at 4:30. I saw one of "Mark's" lithographs in the hotel office, with "Tickets for Sale Here" written in blue pencil oil the margin. It seemed dull and dead about the lobby, and also in the streets. The hotel manager said the Casino, an adjoining hall, was at our service, free, and the keeper had instructions to seat and to light it. Dinner time came; we all went down together. It was "Mark's" first appearance in a public dining room since we started. He attracted some attention as he entered and sat down, but nothing especial. After dinner the news-stand man told me he had not sold a ticket, and no one had inquired about the lecture. I waited until eight o'clock and then went to the hall to notify the man that he need not light up as there would be no audience. The janitor and I chatted until about half-past eight, and I was about to leave when a man and woman came to the door and asked for tickets. I was on the point of telling them that there would be no lecture when I saw a number of people, guests of the hotel, coming. I suddenly changed my mind and told them: "Admission $1; pay the money to me and walk right in." The crowd kept rushing on me, so that I was obliged to ask everybody who could to please have the exact amount ready, as I was unable to change large bills without a good deal of delay. It was after nine o'clock before the rush was over, and I sent a boy for "Mark." He expressed his pleasant surprise. I asked him to walk to the platform and introduce himself, which he did, and I don't believe an audience ever had a better time of an hour and a half. "Mark" was simply immense.

I counted my money while the "show" was going on and found I had taken in $398. When about half through, two young men came to the door and wanted to be admitted for one dollar for the two. I said: "No; one dollar each; I cannot take less." They turned to go; then I called them back and explained that I needed two more dollars to make receipts just $400, and said:

"Now, if you'll pay a dollar each and complete my pile, you can come in and enjoy the best end of the performance, and when the show is out, I'll take you down-stairs and blow you off to twice that amount."

They paid the two dollars, and after the crowd had left, I introduced them to "Mark," and we all went down to the billiard room, had a good time until twelve o'clock, and "Mark" and I made two delightful acquaintances. This has been one of our best days. "Mark" is gaining.

"Mark" is feeling better. He and I left the ladies at the Grand, in Mackinac, and went to Petoskey on the two o'clock boat and train. The smoke, from forest fires on both sides of the track, is so thick as to be almost stifling. There is a good hotel here.

There was a full house, and for the first time in a number of months I had a lecture room so crowded at one dollar a ticket that many could not get standing room and were obliged to go away. The theatre has a seating capacity of five hundred, but over seven hundred and fifty got in. "Mark's" programme was just right -- one hour and twenty minutes long. He stopped at an hour and ten minutes, and cries of "Go on! Go on!" were so earnest that he told one more story. George Kennan was one of the audience. He is going to give a course of lectures at Lake View Assembly, an auxiliary Chautauqua adjoining Petoskey, where about five thousand people assemble every summer. Mr. Hall, the manager, thought that "Mark Twain" would not draw sufficient to warrant engaging him at $250, so I took the risk outside, and won.

"Mark" and I left Petoskey for Mackinac at 5:30 this morning, where we joined the ladies and waited five hours on the dock for S.S. Northwest to take us to Duluth. It was severe on the poor man, but he was heroic and silent all the way. He has not tasted food since the dinner on the Faxton Friday.

On Lake Superior; S. S. Northwest. I was on deck early and found the smoke all gone. In its place was bright sunshine, but it has been so cold all day that few of the other passengers are on deck. Captain Brown and Purser Pierce are doing all they can to hurry us on, for we are eight hours late.

We landed in Duluth at just 9 p.m. Mr. Briggs, our correspondent, met us at the wharf with a carriage. As our boat neared land Briggs shouted:

"Hello, Major Pond!"

"Hello, Briggs!"

"Is Mark Twain all right?"

"Yes; he is ready to go to the hall; he will be the first passenger off the ship."

"Good. We have a big audience waiting for him," said Mr. Briggs.

"We'll have them convulsed in ten minutes," said I.

"Mark" was the first passenger to land. Mr. Briggs hurried him to the church, which was packed with twelve hundred and fifty warm friends (100 degrees in the shade) to meet and greet him. It was a big audience. He got through at 10:50 and we were all on board the train for Minneapolis at 11:20.

It was my busy night. The train for Minneapolis was to start at twelve o'clock. The agents in New York who had fitted me out with transportation and promised that everything should be in readiness on our arrival in Duluth, had forgotten us, and no arrangements for sleeper or transfer of baggage had been made. I had all this to attend to, besides looking after the business part of the lecture, which was on sharing terms with a church society. Everything was mixed up, as the door-tender and finance committee were bound to hear the lecture. I could get no statement, but took all the money in sight, and was on board the train as it was starting for Minneapolis.

We are stopping at the West Hotel; a delightful place. Six skilled reporters have spent about two hours with "Mark." He was lying in bed, and very tired I know, but he was extremely courteous to them and they all enjoyed the interview. The Metropolitan Opera House was filled to the top gallery with a big crowd of well-dressed, intelligent people. It was about as big a night as "Mark" ever had to my knowledge. He introduced a new entertainment, blending pathos with humor with unusual continuity. This was at Mrs. Clemens's suggestion, She had given me an idea on the start that too much humor tired an audience with laughing. "Mark" took the hint and worked in three or four pathetic stories that made the entertainment perfect. The "show" is a triumph, and "Mark" will never again need a running mate to make him satisfactory to everybody.

The next day the Minneapolis papers were full of good things about the lecture. The Times devoted three columns and a half of fine print to a verbatim report of it. The following evening in St. Paul "Mark" gave the same programme, which was commented on in glowing terms by St. Paul papers.

We have had a most charming ride through North Dakota and southeastern Manitoba. It seems as if everything along the route must have been put in order for our reception The flat, wild prairies (uninhabited in 1883) are now all under cultivation. There are fine farmhouses, barns, and vast fields of wheat -- "oceans of wheat," as "Mark" said, as far as eye can reach in all directions, waving like as the ocean waves, and so flat! Mr. Beecher remarked to his wife when riding through here in 1883: "Mother, you couldn't flatter this country."

We had a splendid audience. "Mark" and I were entertained at the famous Manitoba Club after the lecture -- a club of the leading men of Winnipeg. We did not stay out very late, as "Mark" feared Mrs. Clemens would not retire until he came, and he was quite anxious for her to rest, as the long night journey in the cars had been very fatiguing. On our arrival at the hotel we heard singing and a sound of revelry in the parlors. A party of young gentlemen of the lecture committee had escorted our ladies home. They were fine singers, and, with Miss Clara Clemens at the piano, a concert was in progress, that we all enjoyed another hour.

Saturday, the 27th, we all put down as the pleasantest day thus far. Several young English gentlemen who have staked fortunes in this northwest in wheat ranches and other enterprises, brought out their tandems and traps and drove the ladies about the country. They saw the largest herd of wild buffalo that now exists, in a large enclosure. They were driven to various interesting suburban sights, of which there are more than one would believe could exist in this far northwest new city. Bouquets and banks of flowers -- of such beautiful colors! -- were sent in; many ladies called, and all in all it has been an ovation. "Mark," as is his custom, did not get up until time to go to the lecture hall, but he was happy. Several journalists called, who he told me were the best informed and most scholarly lot of editors he had found anywhere, and I think he was correct. There was another large crowd at the lecture, and another and final reception at the famous Manitoba Club. We were home at twelve, and all so happy! We're on the road to happiness surely.

We have been in Crookston, Minn., all day, where we were the first and especially favored guests of this fine new hotel. "Mark Twain's" name was the first on the register. We are enjoying it. "Mark" is as gay as a lark, but he remained in bed until time to go to the Opera House. This city is wonderfully improved since I was here in 1883 with Mr. Beecher, in 1885 with Clara Louise Kellogg, and in 1887 with Charles Dickens, Jr. The opening of this hotel is a great event. People are filling up the town from all directions to see and hear "Mark," and taking advantage of the occasion to see the first new hotel (The Crookston) in their city with hot and cold water, electric lights and all modern improvements.

We left Crookston at 5:40 A.M.; were up at 4:30, Everybody was cheerful; there was no grumbling. This is our first unseasonable hour for getting up, but it has done us all good. Even Clara enjoyed the unique experience. It revived her memory. She recollected that she had telegraphed to Elmira to have her winter cloak expressed to Crookston. Fortunately the agent was sleeping in the express office, near the station. We disturbed his slumbers to find the great cloak, which was another acquisition to our sixteen pieces of hand baggage. Our train was forty-five minutes late. "Mark" complained and grumbled; he persisted that I had contracted with him to travel and not to wait about railway stations at five o'clock in the mornings for late trains that never arrived. He insisted on travelling, so he got aboard the baggage truck and I travelled him up and down the platform, while Clara made a snap shot as evidence that I was keeping to the letter of my contract.

When we boarded the train, we found five lower berths (which means five sections) ready for us. There was a splendid dining car, with meals a la carte, and excellent cooking. All the afternoon there were the level prairies of North Dakota wheat just turning, the whole country a lovely green; then came the arid plains, the prairie-dog towns, cactus, buffalo grass, jack rabbits, wild life and the Missouri River -- dear old friend that had borne both of us on her muddy bosom many a time. It was a great day for both "Mark" and me. The ladies were enthusiastic in proportion as they saw that "Mark" and I were boys again, travelling upon "our native heath."

We arrived at the Park Hotel here at 7:30 A.M. after a good night's sleep. Interest grows more and more intense as we come nearer to the Rocky Mountains. It brings back fond memories of other days. The two Brothers Gibson, proprietors of the hotel, drove our party out to Giant Spring, three miles distant. It is a giant, too. I never saw a more beautiful or more wonderful spring. A big river fairly boils up out of the ground, of the most beautiful deep peacock green color I ever saw in clear water. The largest copper ore smelters in the world are here. The Great Falls could supply power enough for all the machinery west of Chicago, with some to spare.

"Mark" is improving. For the first time since we started he appeared about the hotel corridors and on the street. He and I walked about the outskirts of the town, and I caught a number of interesting snapshots among the Norwegian shanties. I got a good group including four generations, with eight children, a calf and five cats. "Mark" wanted a photograph of each cat. He caught a pair of kittens in his arms, greatly to the discomfort of their owner, a little girl. He tried to make friends with the child and buy the kittens, but she began to cry and beg that her pets might be liberated. He soon captured her with a pretty story, and she finally consented to let them go. Few know "Mark's" great love for cats, as well as for every living creature.

We started at 7:35 A.M. All seem tired. The light air and the long drive yesterday told very much on us all.

"Mark" had an off night and was not at his best, which has almost broken his heart. He couldn't get over it all day. The Gibson Brothers have done much to make our visit delightful, and it has proved very enjoyable indeed. Of course, being proprietors of the hotel, they lose nothing, for I find they charge us five dollars a day each, and the extortions from porters, baggagemen and bellboys surpass anything I know of. The smallest money is two bits (25 cents) here -- absurd!

We enter the Rocky Mountains through a canyon of the Upper Missouri; we have climbed mountains all day, and at Butte are nearly 8,000 feet high. It tells on me, but the others escape. The ladies declare it has been one of the most interesting days of their lives, and "Mark" has taken great interest in everything, but kept from talking. After reaching the hotel, he kept quiet in bed until he went to the hall. He more than made up for last night's disappointment and was at his best. I escorted Mrs. Clemens and Clara to a box in the theatre, expecting to return immediately to the hotel, but I found myself listening, and sat through the lecture, enjoying every word. It actually seemed as if I had never known him to be quite so good. He was great. The house was full and very responsive.

After the lecture many of his former Nevada friends came forward to greet him. We went to a fine club, where champagne and stories blended until twelve, much to the delight of many gentlemen. "Mark" never drinks champagne. His is hot Scotch, winter and summer, without any sugar, and never before 11 p.m.

To-day "Mark" and I went from Butte to Anaconda without the ladies. We left the hotel at 4:30 by trolley car in order to have plenty of time to reach the train, but we had gone only three blocks when the power gave out and we could not move. It was twelve minutes to five and there was no carriage in sight. We tried to get a grocery wagon, but the mean owner refused to take us a quarter of a mile to the depot for less than ten dollars. I told him to go to ---- I saw another grocery wagon near by and told its owner I would pay any price to reach that train. "Mark" and I mounted the seat with him. He laid the lash on his pair of bronchos, and I think quicker time was never made to that depot. We reached the train just as the conductor shouted "All aboard!" and had signalled the engineer. The train was moving as we jumped on. The driver charged me a dollar, but I handed him two.

At Anaconda we found a very fine hotel and several friends very anxiously waiting to meet "Mark." Elaborate arrangements had been made to lunch him and give him a lively day among his old mountain friends, as he had been expected by the morning train. Fortunately he missed this demonstration and was in good condition for the evening. He was introduced by the mayor of the city in a witty address of welcome. Here was our first small audience, where the local manager came out a trifle the loser.

A little incident connected with our experience here shows "Mark Twain's" generosity. The local manager was a man who had known "Mark" in the sixties, and was very anxious to secure him for a lecture in Anaconda. He, therefore, contracted to pay the price asked. Anaconda is a small city, whose chief industry is a large smelting furnace. There were not enough people interested in high-class entertainments to make up a paying audience, and the manager was short about sixty dollars. I took what he had, and all he had, giving him a receipt in full. As "Mark" and I were not equal partners, of course the larger share of the loss fell to him. I explained the circumstances when we had our next settlement at the end of the week, hoping for his approval.

"And you took the last cent that poor fellow had! Send him a hundred dollars, and if you can't afford to stand your share, charge it all to me. I'm not going around robbing poor men who are disappointed in their calculations as to my commercial value. I'm poor, and working to pay debts that I never contracted; but I don't want to get money in that way."

I sent the money, and was glad of the privilege of standing my share. The letter of acknowledgment from that man brought out the following expression from "Mark": "I wish that every hundred dollars I ever invested had produced the same amount of happiness!"

In Helena (August 3d) the people did not care for lectures. They all liked "Mark" and enjoyed meeting him, but there was no public enthusiasm for the man that has made the early history of that mining country romantic and famous all over the world. The Montana Club entertained him grandly after the lecture, and he met many old friends and acquaintances. Some of them had come all the way from Virginia City to see their former comrade of the mining camps. One man, now very rich, came from Virginia City, Nevada, on purpose to see "Mark" and settle an old score. When the glasses were filled, and "Mark's" health proposed, this man interrupted the proceedings by saying:

"Hold on a minute; before we go further I want to say to you, Sam Clemens, that you did me a d--d dirty trick over there in Silver City, and I've come here to have a settlement with you."

There was a deathly silence for a moment, when "Mark" said in his deliberate drawl:

"Let's see. That - was - before - I - reformed, wasn't - it?"

Senator Sanders suggested that inasmuch as the other fellow had never reformed, Clemens and all the others present forgive him and drink together, which all did. Thus "the row was broken up before it commenced" (Buck Fanshaw) -- and all was well. "Mark" told stories until after twelve. We walked from the club to the hotel up quite a mountain, the first hard walk he has had. He stands the light air well, and is getting strong.

The dry burning sun makes life almost intolerable, so that there has been hardly a soul on the streets all day. "Mark" and I had a good time at the Montana Club last night. He simply beats the world telling stories, but we find some bright lights here. There were present Senator Sanders, Major Maginnis, Hugh McQuade, A. J. Seligman, Judge Knowles, of the United States Supreme Court, who introduced Mr. Beecher in Deer Lodge and Butte in 1883; L. A. Walker, Dr. C. K. Cole, A. J. Steele, and Frank L. Sizer. We have very heavy mails, but are all too tired to open and read letters that are not absolutely necessary to be read.

"Mark" lay around on the floor of his room all day reading and writing in his notebook and smoking. In the gloaming Dr. Cole, with his trotters, drove "Mark" and Mrs. Clemens out to Broadwater, four miles. The heat gave way to a delicious balmy breeze that reinvigorated everybody. How delightful are these summer evenings in the Rocky Mountains!

Senator Sanders walked with "Mark" to the station in Helena this morning, while I accompanied the ladies in a carriage. Whom should we meet walking the platform of the station but Mrs. Henry Ward Beecher, on her way to visit her son Herbert in Port Townsend. It was a delightful surprise. Senator Sanders at once recognized her, as in 1883 he joined our party and drove from Helena (then the end of the eastern section of the Northern Pacific Railroad) to Missoula, the eastern end of the western division. We then drove in a carriage with four horses, via Butte and Deer Lodge, and it took four days to make the journey. Senator Sanders travelled the same distance in five hours with us to-day in a Pullman car.

At Missoula we all drove in a "bus" to the Florence House, the ladies inside and "Mark" and I outside with the driver. Here we saw the first sign of the decadence of the horse: a man riding a bicycle alongside the bus, leading a horse to a nearby blacksmith shop. At "Mark's" suggestion I caught a snapshot of that scene. Officers from Fort Missoula, four miles out, had driven in with ambulances and an invitation from Lieutenant-Colonel Burt, commandant, for our entire party to dine at the fort. The ladies accepted. "Mark" went to bed and I looked after the business.

We had a large audience in a small hall, the patrons being mainly officers of the fort and their families. As most of the ladies who marry army officers come from our best Eastern society, it was a gathering of people who appreciated the occasion. After the lecture, the meeting took the form of a social reception, and it was midnight before it broke up. The day has been one of delight to all of us. As we leave at 2:30 P.M. to-morrow, all have accepted an invitation to witness guard-mounting and lunch early at the fort.

Two ambulances were sent to the hotel for our party and Adjutant-General Ruggles, who is here on a tour of inspection. "Mark" rose early and said he would walk to the fort slowly; he thought it would do him good. General Ruggles and the ladies went in one ambulance (the old four-mule army officers' ambulance) and the other waited some little time before starting, that I might complete arrangements for all the party to go direct from the fort to the depot. I was the only passenger riding with the driver, and enjoying the memory of like experiences on the plains when in the army. We were about half way to the fort when I discovered a man walking hurriedly toward us quite a distance to the left. I was sure it was "Mark," and asked the driver to slow up. In a minute I saw him signal us, and I asked the driver to turn and drive toward him. We were on a level plain, and through that clear mountain atmosphere one can see a great distance. We were not long in reaching our man, much to his relief. He had walked out alone and taken the wrong road, and after walking five or six miles on it, discovered his mistake, and was countermarching when he saw our ambulance and ran across lots to meet us. He was tired -- too tired to express disgust -- and sat quietly inside the ambulance until we drove up to headquarters, where were a number of officers and ladies, besides our party. As "Mark" stepped out, a colored sergeant laid hands on him, saying:

"Are you 'Mark Twain'?"

"I am," he replied.

"I have orders to arrest and take you to the guardhouse."

"All right."

And the sergeant walked him across the parade ground to the guardhouse, he not uttering a word of protest.

Immediately Lieutenant-Colonel Burt and the ambulance hurried over to relieve the prisoner. Colonel Burt very pleasantly asked "Mark's" pardon for the practical joke and invited him to ride back to headquarters. "Mark" said:

"Thanks, I prefer freedom, if you don't mind. I'll walk. I see you have thorough discipline here," casting an approving eye toward the sergeant who had him under arrest.

The garrison consisted of seven companies of the Twenty-seventh United States Colored Regiment. There was a military band of thirty pieces. Guard mount was delayed for General Ruggles' and our inspection. The band played quite a programme, and all declared it one of the finest military bands in America. We witnessed some fine drilling of the soldiers, and learned that for this kind of service the colored soldiers were more subordinate and submissive to rigid drill and discipline than white men, and that there were very few desertions from among them.

Attached to our train from Missoula station were two special cars, bearing an excursion party consisting of the new receiver of the Northern Pacific Railroad and his friends, one of whom we were told was the United States Supreme Court Judge who had appointed this receiver. An invitation was sent in to "Mark" to ride in their car, but as it came for him alone and did not include the ladies, he declined.

It was an enjoyable ride to Spokane, where we arrived at 11:30, and put up at the Spokane House, the largest hotel I ever saw. It was a large commercial building, covering an entire block, revamped into a hotel. A whole store was diverted into one bedroom, and nicely furnished, too. Reporters were in waiting to interview the distinguished guest. "Mark" is gaining strength and is enjoying everything, so the interviewers had a good time.

We spent all day, August 8th, in Spokane. The hotel was full. The new receiver and his gay party are also spending the day here, but all leave just before the time set for the lecture.

In the forenoon "Mark" and I walked about this remarkable city, with its asphalt streets, electric lights, nine-story telegraph poles, and commercial blocks that would do credit to any Eastern city. There were buildings ten stories high, with the nine top stories empty, and there were many fine stores with great plate-glass fronts, marked "To Rent." In the afternoon our entire party drove about the city in an open carriage. Our driver pointed out some beautiful suburban residences and told us who occupied them.

"That house," he said, as we drove by a palatial establishment, "is where Mr. Brown lives. He is receiver for the Spokane Bank, which failed last year for over $2,000,000. You all know about that big failure, of course. The receiver lives there."

Pointing out another house, he said: "That man living up in that big house is receiver for the Great Falls Company. It failed for nearly a million. The president and directors of that company are most all in the State prison. And this yere house that we are coming to now is where the receiver of the Washington Gas and Water Company lives," etc.

"Mark" said to the ladies: "If I had a son to send West, I would educate him for a receiver. It seems to be about the only thriving industry."

We found here a magnificent new theatre -- the Opera House. It has cost over $200,000 and was never yet a quarter filled. The manager was greatly disappointed at the receipts for the lecture; he had counted on a full house. Where he expected the people to come from I don't know. The receipts were not much better than in Missoula. "Mark" didn't enjoy it, and manifested no delicacy in so expressing himself.

As we have a day here, the ladies have overhauled and repacked their trunks. I think there is no occupation that has the fascination for women when travelling as the unpacking and overhauling of large travelling trunks. They go at it early, miss their luncheon, and are late to dinner, and yet show no signs of fatigue.

There was another incident here. Our ladies dressed their best for dinner, and outshone the receiver's excursionists, who occupied most of the great dining hall. "Mark" didn't see it, as he never comes down to dinner. I know I saw it, and enjoyed a feeling of pride. I just felt and knew I was envied by the men at the other tables. Clara Clemens is a beautiful girl. As we passed out of the dining room into the great parlor, she sat down to the Chickering grand piano and began playing a Chopin nocturne. It was in the gloaming, Stealthily guests came in from dinner and sat breathlessly in remote parts of the boundless room listening to a performance that would have done credit to any great pianist. Never have I witnessed a more beautiful sight than this sweet brunette unconsciously holding a large audience of charmed listeners. If it was not one of the supreme moments of her mother's life, who saw and heard her, then I have guessed wrong. It was an incident forever fixed in my memory.

That night at 11:30 we went aboard the sleeper on the Great Northern Road. Everything was in readiness for us. The next day was one full of interest as we rode over the Rockies on the zigzag road, travelling over thirty miles to make seven. "Mark" rode on the engine, greatly to the delight of the engineer.

We transferred at Seattle to the little "Greyhound of Puget Sound" -- The Flyer -- said to be the fastest steamer in the world. "Mark" sat on the deck of The Flyer watching the baggage-smashers removing our trunks from the baggage car to the truck which was to convey them to The Flyer, and exclaimed: "Oh, how I do wish one of those trunks were filled with dynamite and that all the baggage-destroyers on earth were gathered about it, and I just far enough off to see them hurled into Kingdom Come!"

We arrived in Tacoma at five o'clock, and have sumptuous apartments at The Tacoma, a grand caravansery built by the Northern Pacific Railroad Company. The "receiver" is an old friend of mine, formerly a contractor on the Northern Pacific Railroad. I also found another old friend in C. H. Prescott -- one of the prosperous. He is local "receiver" of the Northern Pacific Railroad, the highest distinction a man can attain out here. This is another overgrown metropolis. We can't see it, nor anything else, owing to the dense smoke everywhere.

Here in Tacoma the ladies are to remain and rest, while "Mark" and I take in Portland and Olympia.

At Tacoma early this morning Mr. S. E. Moffett, of the San Francisco Examiner, appeared. He is "Mark's" nephew and resembles his uncle very much. On his arrival "Mark" took occasion to blaspheme for a few minutes, that his relative might realize that men are not all alike. He cursed the journey, the fatigues and annoyances, winding up by acknowledging that if everything had been made and arranged by the Almighty for the occasion, it could not have been better or more comfortable, but he "was not travelling for pleasure," etc.

He and I reached Portland on time, 8:22, and found the Marquam Grand packed with a waiting audience and the sign "Standing Room Only" out. The lecture was a grand success. After it "Mark's" friend, Colonel Wood, formerly of the United States army, gave a supper at the Portland Club, where about two dozen of the leading men were entertained for two hours with "Mark's" story-telling. They will remember that evening as long as they live. There is surely but one "Mark Twain."

Smoke, smoke, smoke! It was not easy to tear ourselves away from Portland so early. The Oregonian contains one of the best notices that "Mark" has had. He is pleased with it, and is very jolly to-day.

We left for Olympia at eleven o'clock, via Northern Pacific Railroad. Somehow "Mark" seems to grow greater from day to day. Each time it seemed as though his entertainment had reached perfection, but last night surpassed all. A gentleman on the train, a physician from Portland, said that no man ever left a better impression on a Portland audience; that "Mark Twain," was the theme on the streets and in all business places. A young reporter for The Oregonian met "Mark," as he was boarding the train for Olympia, and had probably five minutes' talk with him. He wrote a two-column interview which "Mark" declared was the most accurate and the best that had ever been reported of him.

On the train a bevy of young ladies ventured to introduce themselves to him, and he entertained them all the way to Olympia, where a delegation of leading citizens met us, headed by John Miller Murphy, editor of the oldest paper in Washington. They met us outside the city, in order that we might enjoy a ride on a new trolley car through the town. As "Mark" stepped from the train, Mr. Miller said:

"Mr. Twain, as chairman of the reception committee, allow me to welcome you to the capital of the youngest and most picturesque State in the Union. I am sorry the smoke is so dense that you cannot see our mountains and our forests, which are now on fire."

"Mark" said: "I regret to see -- I mean to learn (I can't see, of course, for the smoke) that your magnificent forests are being destroyed by fire. As for the smoke, I do not so much mind. I am accustomed to that. I am a perpetual smoker myself."

I had trouble in settling at the Opera House; the manager is a scamp. I expected trouble, and I had it.

The Tacoma Press Club gave "Mark" a reception in their rooms after the lecture, which proved to be a very bright affair. "Mark" is finding out that he has found his friends by the loss of his fortune. People are constantly meeting him on the street, at halls, and in hotels, and telling him of the happiness he has brought them -- old and young alike. He seems as fresh to the rising generation as he is dear to older friends. Here we met Lieutenant-Commander Wadhams, who is executive officer of the Mohican, now in Seattle harbor. He has invited us all on board the man-of-war to dine to-morrow, and we have all accepted.

"Mark" had a great audience in Seattle the next evening. The sign "Standing Room Only" was out again. He was hoarse, but the hoarseness seemed to augment the volume of his voice. After the lecture he met many of his friends and admirers at the Rainier Club. Surely he is finding out that his misfortunes are his blessings. He has been the means of more real pleasure to his readers and hearers than he ever could have imagined had not this opportunity presented itself.

"Mark's" cold is getting worse (the first cold he ever had). He worried and fretted all day; two swearing fits under his breath, with a short interval between them, they lasted from our arrival in town until he went to sleep after midnight. It was with great difficulty that he got through the lecture. The crowd, which kept stringing in at long intervals until half-past nine, made him so nervous that he left the stage for a time. I thought he was ill, and rushed back of the scenes, only to meet him in a white rage. He looked daggers at me, and remarked:

"You'll never play a trick like this on me again. Look at that audience. It isn't half in yet."

I explained that many of the people came from long distances, and that the cars ran only every half hour, the entire country on fire causing delays, and that was why the last installment came so late. He cooled down and went at it again. He captured the crowd. He had a good time and an encore, and was obliged to give an additional story.

"Mark's" throat is in a very bad condition. It was a great effort to make himself heard. He is a thoroughbred -- a great man, with wonderful will power, or he would have succumbed. We had a fine audience, a crowded house, very English, and I think "Mark" liked it. Everything here is English and Canadian. There is a rumor afloat that the country about us is beautiful, but we can't see it, for there is smoke, smoke everywhere, and no relief. My eyes are sore from it. We are told that the Warrimoo will not sail until Wednesday, so I have arranged for the Victoria lecture Tuesday.

Our tour across the continent is virtually finished, and I feel the reaction. "Othello's occupation gone." This morning "Mark" had a doctor, who says he is not seriously ill. Mrs. Clemens is curing him. The more I see of this lady the greater and more wonderful she appears to be. There are few women who could manage and absolutely rule such a nature as "Mark's." She knows the gentle and smooth way over every obstruction he meets, and makes everything lovely. This has indeed been the most delightful tour I have ever made with any party, and I wish to record it as one of the most enjoyable of all my managerial experiences. I hardly ever expect another. "Mark" has written in a presentation copy of "Roughing It":

"Here ends one of the smoothest and pleasantest trips across the continent that any group of five has ever made."

"Mark" is better this evening, so we shall surely have a good lecture in Victoria.

We are all waiting for the news as to when the Warrimoo will be off the dry dock and ready to sail. "Mark" is getting better. I have booked Victoria for Tuesday, the 20th.

"Mark" has lain in bed all day, as usual, spending much time writing. Reporters have been anxious to meet and interview him, and I urged it, He finally said: "If they'll excuse my bed, show them up."

A quartet of bright young English journalists came up. They all had a good time, and made much of the last interview with "Mark Twain" in America, as it was. "Mark" was in excellent spirits. His throat is better.

We are at Vancouver still, and the smoke is as firmly fixed as we are in the town. It is bad. "Mark" has not been very cheerful to-day. He doesn't get his voice back. He and I took a walk about the streets, and he seemed discouraged, I think on account of Mrs. Clemens's dread of the long voyage, and because of the unfavorable stories we have heard of the Warrimoo. We leave Vancouver, and hosts of new friends, for Victoria, B.C., and then we part. That will not be easy, for we are all very happy. It makes my heart ache to see "Mark" so downhearted after such continued success as he has had.

On August 20th the boat for Victoria arrived half an hour late. We all hurried to get on board, only to be told by the captain that he had one hundred and eighty tons of freight to discharge, and that it would be four o'clock before we left. This lost our Victoria engagement, which I was obliged to postpone by telegraph. "Mark" was not in condition to relish this news, and as he stood on the wharf after the ladies had gone aboard he took occasion to tell the captain, in very plain and unpious language, his opinion of a passenger-carrying company that, for a few dollars extra, would violate their contract and obligations to the public. They were a lot of -- somethings, and deserved the penitentiary. The captain listened without response, but got very red in the face. It seems the ladies had overheard the loud talk. Soon after "Mark" joined them he came to me and asked if I wouldn't see that captain and apologize for his unmanly abuse, and see if any possible restitution could be made. I did so, and the captain and "Mark" became quite friends.

We left Vancouver on The Charmer at six o'clock, arriving in Victoria a little after midnight.

"Mark" has been in bed all day; he doesn't seem to get strength. He smokes constantly, and I fear too much also; still, he may stand it. Physicians say it will eventually kill him.

We had a good audience. Lord and Lady Aberdeen, who were in a box, came back on the stage after the lecture and said many very nice things of the entertainment, offering to write to friends in Australia about it. "Mark's" voice began strong, but showed fatigue toward the last. His audience, which was one of the most appreciative he ever had, was in great sympathy with him as they realized the effort he was obliged to make, owing to his hoarseness.

A telegram from Mr. George McL. Brown says the Warrimoo will sail at six o'clock to-morrow evening. This is the last appearance of "Mark Twain" in America for more than a year I know, and I much fear the very last, for it doesn't seem possible that his physical strength can hold out. After the lecture to-night he expected to visit a club with Mr. Campbell, who did not come around. He and I, therefore, went out for a walk. He was tired and feeble, but did not want to go back to the hotel. He was nervous and weak, and disappointed, for he had expected to meet and entertain a lot of gentlemen. He and I are alike in one respect -- we don't relish disappointment.

We are in Victoria yet. The blessed "tie that binds" seems to be drawing tighter and tighter as the time for our final separation approaches. We shall never be happier in any combination, and Mrs. Clemens is the great magnet. What a noble woman she is! It is "Mark Twain's" wife who makes his works so great. She edits everything and brings purity, dignity, and sweetness to his writings. In "Joan of Arc" I see Mrs. Clemens as much as "Mark Twain."

"Mark" and I were out all day getting books, cigars, and tobacco. He bought three thousand Manilla cheroots, thinking that with four pounds of Durham smoking tobacco he could make the three thousand cheroots last four weeks. If perpetual smoking ever kills a man, I don't see how "Mark Twain" can expect to escape. He and Mrs. Clemens, an old friend of "Mark's" and his wife, now living near here, went for a drive, and were out most of the day. This is remarkable for him. I never knew him to do such a thing before.

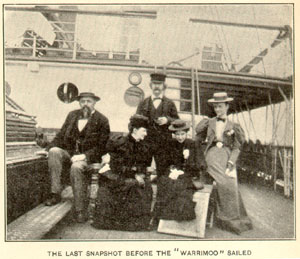

The Warrimoo arrived about one o'clock. We all went on board and lunched together for the last time. Mrs. Clemens is disappointed in the ship. The whole thing looks discouraging, and our hearts are almost broken with sympathy for her. She tells me she is going to brave it through, for she must do it. It is for her children. Our party got out on the deck of the Warrimoo, and Mr. W. G. Chase, a passenger, took a snapshot of our quintette. Then wife and I went ashore, and the old ship started across the Pacific Ocean with three of our most beloved friends on board. We waved to one another as long as they kept in sight.

Before sailing "Mark Twain" wrote a letter to the editor of the San Francisco Examiner, from which I quote:

"Now that I reflect, perhaps it is a little immodest in me to talk about my paying my debts, when by my own confession I am blandly getting ready to unload them on the whole English-speaking world. I didn't think of that -- well, no matter, so long as they are paid.

"Lecturing is gymnastics, chest-expander, medicine, mind healer, blues destroyer, all in one. I am twice as well as I was when I started out. I have gained nine pounds in twentyeight days, and expect to weigh six hundred before January. I haven't had a blue day in all the twenty-eight. My wife and daughter are accumulating health and strength and flesh nearly as fast as I am. When we reach home two years hence, we think we can exhibit as freaks." Mark Twain. Vancouver, B.C., August 15, 1895.

On September 17, 1897, he wrote me from Weggis, Lake Lucerne:

"I feel quite sure that in Cape Town, thirteen months ago, I stood on a platform for the last time. Nothing but the Webster debts could persuade me to lecture again, and I have ceased to worry about those. You remember in the Sam Moffett interview in Vancouver, in 1895, I gave myself four years in which to make money enough to pay those debts -- and that included two lecture seasons in America, one in England, and one around the world. But we are well satisfied now that we shall have those debts paid off a year earlier than the prophecy, if I continue able to work as I have been working in London and here, and without any further help from the platform. And so it is, as I said a moment ago, I am a cheerful man these days."

In another letter he said: "I managed to pull through that long lecture campaign, but I was never very well, from the first night in Cleveland to the last one in Cape Town, and I found it pretty hard work on that account. I did a good deal of talking when I ought to have been in bed. At present I am not strong enough for platform work, and am not going to allow myself to think of London, or any other platform, for a long time to come. It grieves me, for. I could make a satisfactory season in London and America now that I am practised in my trade again."

On April 4, 1899, he wrote me from Vienna: "No; I don't like lecturing. I lectured in Vienna two or three weeks ago, and in Budapest last week, but it was merely for fun, not for money. I charged nothing in Vienna, and only the family's expenses in Budapest. I like to talk for nothing, about twice a year; but talking for money is work, and that takes the pleasure out of it. I do not believe you could offer me terms that would dissolve my prejudice against the platform. I do not expect to see a platform again until the wolf commands. Honest people do not go robbing the public on the platform, except when they are in debt. (Disseminate this idea; it can do good)."

In the autumn of 1895 I wanted him to give fifty lectures in England, but he thought it would not be worth his while. His book was the next thing to be thought of and planned for. Four years later, while he was in Sweden, I again suggested lecturing at a thousand dollars a night. "I think there's stuff in 'Following the Equator' for a lecture, but I can't come," he wrote.

As a letter writer "Mark Twain" is inimitable. He writes with the same unconventionality with which he talks, and his letters are the man.

"DEAR POND:

0, b'gosh, I can't. I hate writing.

is characteristic. He is always humorous. Once he arranged for a donkey to be sent to the Elmira summer home for one of the children to ride. He acknowledged the receipt. "Much obliged, Homer, for the jackass. Tell Redpath I shall not want him now." Of course the latter reference was to a business matter, but the conjunction was irresistible. In the autumn of 1899 he wrote to me: "I'm not going to barnstorm the platform any more, but I am glad you have corralled Howells. He's a most sinful man, and I always knew God would send him to the platform if he didn't behave."

In another letter he writes: "Say! Some time ago I received notice that I had been elected honorary member of the 'Society of Sons of Steerage Immigrants,' and was told that Kipling, Hop Smith, and Nelson Page are officers of it. What right have they to belong? Ask Page or Smith about it."

But it is not always fun. His business letters are clear and straightforward. He understood how to deal with his audiences and to meet requirements with the utmost honesty. But his "nerves" were readily worn out on the surface, one of his horrors was delay in beginning and the late comers who always interrupt. He devised small programmes, printed on stiff card paper, so that they could neither be used as fans nor rustle, which is so annoying to a person on the platform.

He and Cable were always friends, but the novelist never could resist the temptation to lengthen the reading of his selections, and this made a constant friction, because it necessarily curtailed the time left for "Mark," sensitive ever to the obligation he felt to the audiences.

Throughout the scores of letters in my possession there are constant and charming references to his wife and children; unpremeditated in expression, and therefore the more valuable. His hospitable spirit is also as fully exhibited. He has the keenest sense of personal honor, as well as of his own rights.

I had received a letter from the Secretary of War notifying me that by order of the President a Congressional medal of honor had been presented to me for "most distinguished gallantry in action" -- gallantry thirty-seven years ago. I was so proud that I wrote Mark about it. He wrote me from Austria, June 17, 1898, in reply

"DEAR POND: My, it's a long jump from the time you played solitaire with your cannon! Yes, I should think you would want to go soldiering again. Old as I am, I want to go to the war myself. And I should do it, too, if it were not for the danger.

"To-day we ought to get great news from Cuba. I am watching for the Vienna evening papers. This is a good war with a dignified cause to fight for. A thing not to be said of the average war."

"Mark Twain" eats only when he is hungry. I have known him to go days without eating a particle of food; at the same time he would be smoking constantly when he was not sleeping. He insisted that the stomach would call when in need, and it did. I have known him to sit for hours in a smoking car on a cold day, smoking his pipe and reading his German book with the window wide open. I said once: "Mark, do you know it's a cold day and you are exposing yourself before that open window, and you are booked to lecture tonight?"

"I do know all about it. I am letting some of God's fresh air into my lungs for that purpose. My stomach is all right, and under these conditions I am not afraid of taking cold."

"But," said I, "the car is cold, and you are making the passengers uncomfortable by insisting on that window being wide open."

"They deserve to be uncomfortable for not knowing how to live and take care of themselves." He closed the window, however.

"Mark" seldom had a cold, and with the exception of carbuncles was never ill.

"Pudd'n Head Wilson" was first acted by Frank Mayo, of whom "Mark's" appreciation was very sincere. While seeing the play for the first time, at the Herald Square Theatre, the audience discovered "Mark" in a box, and vociferously called: "Mark Twain! Mark Twain!" He rose up and said:

"I am sure I could say many complimentary things about this play which Mr. Mayo has written and about his portrayal of the chief character in it, and keep well within the bounds both of fact and of good taste; but I will limit myself to two or three. I do not know how to utter any higher praise than this: that when Mayo's 'Pudd'n Head' walks this stage here, clothed in the charm of his gentle charities of speech, and acts the sweet simplicities and sincerities of his gracious nature, the thought in my mind is: 'Why, bless your heart, you couldn't be any dearer or lovelier or sweeter than you are without turning into that man whom all men love, and even Satan is fond of -- Joe Jefferson.'"

In May, 1895, he wrote to me from Paris: "Frank Mayo has done a great thing for both of us; for he has proved himself a gifted dramatist as well as a gifted orator, and has enabled me to add another new character to American drama. I hope he will have grand success."

The serious side of "Mark Twain" is shown in the following letter to a woman whose sister wished to go upon the lecture platform; this letter went the rounds of the press years ago, but it should be kept alive. I reproduce it, as it points a moral:

"I have seen it tried many and many a time. I have seen a lady lecturer urged upon the public in a lavishly complimentary document signed by Longfellow, Whittier, Holmes, and some others of supreme celebrity, but there was nothing in her, and she failed. If there had been any great merit in her, she never would have needed those men's help; and (at her rather mature age) would never have consented to ask it.

"There is an unwritten law about human successes, and your sister must bow to that law. She must submit to its requirements. In brief, this law is:

1. No occupation without an apprenticeship.

2. No pay to the apprentice.

"This law stands right in the way of the subaltern who wants to be a general before he has smelt powder; and it stands (and should stand) in everybody's way who applies for pay and position before he has served his apprenticeship and proved himself.

"Your sister's course is perfectly plain. Let her enclose this letter to Major J. B. Pond, Everett House, New York, and offer to lecture a year for $10 a week and her expenses, the contract to be annullable by him at any time after a month's notice, but not annullable by her at all; the second year, he to have her services, if he wants them, at a trifle under the best price offered by anybody else.

"She can learn her trade in those two years, and then be entitled to remuneration; but she cannot learn it in any less time than that, unless she is a human miracle.

"Try it, and do not be afraid. It is the fair and right thing. If she wins, she will win squarely and righteously, and never have to blush."

No man has ever written whose humor has so many sides, or such breadth and reach. His passages provoke the joyous laughter of young and old, of learned and unlearned, and may be read the hundredth time without losing, but rather multiplying, in power. Sentences and phrases that seem at first made only for the heartiest laughter, yield at closer view a sanity and wisdom that are good for the soul. He is also a wonderful story-teller. Thousands of people can bear testimony that the very humor which has made him known all over the world is oftentimes swept along like the debris of a freshet by the current of his fascinating narrative. His later works, like "The Yankee at King Arthur's Court" and Joan of Arc," show that he has studied and apprehends also the great problems of modern life as well as those of history. Mark is personally as human as his humor; as tender and sensitive to the aspirations of the mind as in his daily living.

Business relations and travelling bring out the nature of a man. After my close relations with "Mark Twain" for sixteen years, I can say that he is not only what the world knows him to be, a humorist, a philosopher, and a genius, but a sympathetic, honest, brave gentleman.

MARK TWAIN and GEORGE W. CABLE travelled together one season. Twain and Cable, a colossal attraction, a happy combination! Mark owned the show, and paid Mr. Cable $600 a week and his travelling and hotel expenses. The manager took a percentage of the gross receipts for his services, and was to be sole manager. If he consulted the proprietor at all during the term of the agreement, said agreement became null and void.

These "twins of genius," as I advertised them, were delightful company. Both were Southerners, born on the shores of the Mississippi River, and both sang well. Each was familiar with all the plantation songs and Mississippi River chanties of the negro, and they would often get to singing these together when by themselves, or with their manager for sole audience.

So delightful were these occasions, and so fond were they of embracing every private opportunity of "letting themselves out," that I often instructed our carriage driver to take a long route between hotels and trains that I might have a concert which the public was never permitted to hear.

Mr. Cable's singing of Creole songs was very charming and novel. They were so sweet, and he sang so beautifully, that everybody was charmed, it was all so simple, and quaint, and dignified.

[The manuscripts of Eccentricities of Genius are in the Barrett Collection. They include two versions of the chapter that Pond wrote on George Washington Cable. In the first version of that chapter he'd written this further account of the tour:

"When the Mark Twain and George Washington Cable combination was organized in 1885, in their joint program Mr. Cable became a student of Mark and fell to aping him to such an extent as to make him appear ridiculous. He assumed Mark's drawl in his readings and it became almost a second nature to him to the extent that he was imitating Mark even in his conversation, and Mr. Cable has since acknowledged to me that that fault of imitation, and that drawl, had injured him for platform work."

Pond sent the chapter to Cable for his approval. Cable disapproved of much that Pond wrote: the manuscript pages are often covered with his fastidious objections in pencil. He was especially upset with this passage on MT's influence. Next to the first sentence he wrote: "It is a shame for you to write this. It's tone is positively vindictive." And at the end of the passage he wrote, in the margins and on the back of Pond's manuscript: "I never desired to imitate Mark Twain's manner and never consciously adopted it for a moment. We were together night and day, for seventy days, and if I unconsciously caught up a trick or two of his manner of speech it was natural I should. But it was never intentional, and this acknowledgment is all the acknowledgment I ever made to you. I think it not unlikely that Mark Twain may have as unconsciously caught a trick or two of my manners. I never said any such thing had injured me for platform work; for I am not aware that it ever did so. It was a momentary contagion of outward manner, which I cast off the moment it was called to my attention."

The published Eccentricities of Genius omits all mention of the tour in the Cable chapter.]