|

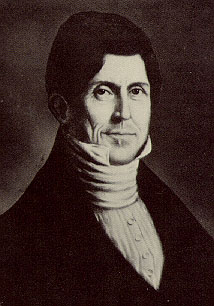

Ransy Sniffle |

The ring-tailed roarer appears in early Southwestern humor as one of Augustus Longstreet's most unforgettable characters, Ransy Sniffle. Sniffle is one of the first great clowns of Southwestern humor, appearing in "The Fight" from the Southwestern classic _Georgia Scenes_ in 1835. Sniffle is the first in a long line of ugly, violent and comical anti-heroes of this genre. Within "The Fight", he is a sinister character who corrupts the more respectable characters of Stallions and Durham through his deception. Sniffle's appearance is in keeping with his qualities--described by the narrator as having,

fed copiously upon red clay and blackberries. This diet had given to Ransy a complexion that a corpse would have disdained to own, and an abominal rotundity that was quite unprepossessing. Long spells of the fever and ague, too, in Ransy's youth, had conspired with clay and blackberries to throw him quite out of the order of nature. His shoulders were fleshless and elevated; his head large and flat; his neck slim and translucent; and his arms, hands, fingers, and feet were lengthened out of all proportion to the rest of his frame. His joints were large and his limbs small; and as for flesh, he could not, with propriety, be said to have any. Those parts which nature usually supplies with the most of this article--the calves of the legs, for example-presented in him the appearance of so many well-drawn blisters. His height was just five feet nothing; and his average weight in blackberry season, ninety-five.

Ransy and the other characters in Longstreet's stories are first generation frontiersmen and are identified with robust, even gaudy, personalities which dominate the inner stories. The trademark of southwestern humorists is often their use of the frame narrative. Longstreet uses this device, even in early humor, to accomodate the unfolding of the story as told by a typically aristocratic and composed narrative voice. This form enables the reader to observe the violent fight through a superior and disconnected vantage point, thus permitting the reader to laugh at savage or grotesque behavior and characters. It also creates a position on either end of the story for the author's viewpoints and analysis to appear in a direct and forthright manner. At the close of "The Fight", Longstreet writes, "Thanks to the Christian religion, to schools, colleges and benevolent associations, such scenes of barbarism and cruelty as that which I have been just describing are now of rare occurence." Once again taking the reader out of any place of sympathy or responsibility and allowing the story--though professed to be a realistic picture of Georgia--to simply laugh and move on.