|

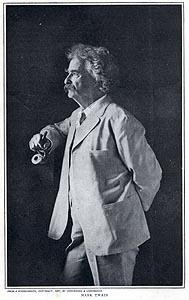

He is the most widely known American

writer of his time. In the interest and attention of

foreign readers he ranks with Cooper, Mrs. Stowe, and Poe;

among Americans none is better known by other peoples save

Washington, Lincoln, and President Roosevelt. To this host

of readers beyond the sea and to the host of readers at

home he is known chiefly as a humorist; but it may be

suspected that fifty years hence, when his unique

personality and laughter-provoking manner and mental

attitude have become traditions, there will emerge a

reputation based securely on a little group of books which

many of those who are familiar with his later work have

never read.

When Mark Twain was born, the first great

tide of emigration, which had gathered itself in quiet

places along the Atlantic seaboard, and sent manifold

streams through the passes of the Alleghanies, and

fertilized the vast central valley of the continent, had

touched the edges of the plains; and the man of prophetic

mind, discerning the significance of its high-water marks,

might have foreseen the second great wave which, after the

close of the Civil War, was to sweep from the prairies

across the Plains to the Pacific and obliterate the Great

American Desert that stretched, like a vast blight, across

the old school maps. St. Louis was so small a town that

Mark Twain has somewhere remarked that he could have bought

it for a million dollars if he had happened to have the

money at hand; there were great lonely wastes. which later

were to be fertile and populous; but when the creator of

Tom Sawyer was a boy in Hannibal, Missouri, the Mississippi

Valley was under human control, the river was crowded with

craft of many kinds, and a unique habit of life had been

developed along its banks. Of this primitive and powerful

outgo of human energy and activity the river was both the

occasion and the shaping force. The majesty of it appealed

to the earliest voyagers, but its magnitude can only be

seen by the imagination; for it drains half a continent, is

fed by fifty-four navigable streams and by several hundred

more of sufficient depth to float craft of light draught.

It penetrated and opened up to trade and travel the very

heart of the continent; it was separated by many days' hard

travel from the early settlements on the seaboard news of

the older world was slow in getting to the river

population, and they were not much influenced by it.

The cry "Westward Ho," heard on the Thames

in Shakespeare's time, had summoned the adventurous, the

restless, the lawless, from the older communities north and

south and sent them into the immense section drained by the

Mississippi. The East from which they came was still in the

provincial stage of its growth, with its eyes toward

Europe; the Southwest that was to be soon detached itself

from the ideas and interests of the older world and boldly

gave itself up to the work at hand and to the manner of

life which its new conditions and tasks rapidly fashioned.

The earlier immigrants had brought with them a complete

stock of religious and social standards, which were

gradually subdued to the new soil; the men of the

Mississippi Valley were deeply affected by certain

fundamental ideas of conduct, but they were very little

embarrassed by external conventions of manner, dress, or

speech. They developed the primitive virtues of courage,

resourcefulness, self-reliance, a sense of reality

impatient of the circumlocutions of formality, a speech

which gained in vigor and vividness what it lost in breadth

of expression. Men went straight at the fact, and brushed

aside everything that hindered the shortest and swiftest

hitting of the nail on the head. On the river a vast and

appalling profanity was developed, but it was less a matter

of conscious irreverence than of surplus imagination and a

primitive instinct for the picturesque. A few oaths are

binding, many are loosening; and the profanity of the

Mississippi Valley was largely "giving the imagination a

loose." Conditions were hard and work was harder;

vocabularies were limited and, beyond the demands of

routine activity, inadequate; exigencies of all kinds

evoked a variety and force of expression to which the

resources of profanity were equal. In the Far East cursing

is a solemn and elaborate ritual of imprecation, casting

the shadow of a terrible blight on one's remotest ancestors

and projecting it over one's fathest descendants. It

shadows one's entire racial career. In the Mississippi

Valley, on the other hand, cursing was mainly an illicit

use of picturesque language, or a reckless excursion into

the realms of humor. Life was essentially fraternal and

kindly; a broad, genial humor underlay and enfolded it, and

much of the profanity was fundamentally humorous. Its

interest lay in the striking effects of broad contrasts; it

reveled in audacious comparisons, far-fetched similes,

epithets that overflowed with suggested insult.

The life of the river and of the

communities that were tributary to it was probably as

democratic as any the world has known. The squire, who was

usually of Virginia or Kentucky descent, and was believed

to be "worth" twenty-five or thirty thousand dollars, but,

as a matter of courtesy, was credited with the possession

of fifty thousand, was looked up to in a way, but without a

particle of subservience. Every other man in the community

was as good as he, only less fortunate. There was thrift,

but very little greed; great wealth was unknown, but it was

easy to make a living. Everybody was religious, but the

current form of religion, although bristling with

theoretical difficulties, was of a very comfortable sort

and full of adaptations to local conditions. In Hannibal,

when Mark Twain was a boy, the Presbyterians, Baptists, and

Methodists were, he says, "the three religious disorders."

He heard Presbyterian preaching for family reasons, but he

went to the Methodist Sunday-school because "the terms were

easier." There was a good deal of profanity, drinking, and

loafing, but the more sophisticated forms of immorality

were unknown. Certain points of conduct were also points of

honor; the statute of limitations ran against legal but not

against moral responsibility for debts; there was a spirit

of universal kindliness and a charity which enfolded even

the town drunkard, and treated him not as an outcast but as

a ward of the community and an illicit local institution.

He was a weaker brother, whose sins were condoned because

he belonged to the family. Society in the Mississippi

Valley in Tom Sawyer's time was a pure democracy, in easy

circumstances, free from anxiety, charitable of everything

except cowardice and meanness, taking life comfortably,

with a broad margin of humor. It was as free from

introspection as if Puritanism had never brooded over its

sins and worried about its soul; it was as unconscious of

traditional standards and classical models as Adam and Eve

in the Garden of Innocence, and it led a happy-go-lucky

life with serene trust in the good faith of Providence and

in the square deal at the hands of the ruler of the

universe. The light-hearted industry and contagious force

which mastered the perils of the river and gave it a vast

neighborliness are thrown into striking relief by the

somber and sordid temper and the tragic conditions of life

on the Volga as they have been drawn in black and white by

Gorky.

Of this old-time life under conditions

which will never be reproduced, Mark Twain was the

interpreter and recorder, and long after he has ceased to

be remembered as a fun-maker he will remain the historian

in a vital dialect of the early Mississippi Valley. . .

.

Mark Twain is so much a world-figure and

so entirely the product of the old-time Mississippi Valley

life, with its vast friendliness and its unconventional

intimacy, that the extraordinary frankness and detail of

the autobiography which he is now publishing need not

disturb the more reticent and circumspect; like those very

early ancestors of ours whose diaries he has edited, he has

nothing to conceal or be ashamed of, and the material which

he is storing up with a prodigal hand will enrich some

future biographer beyond the dreams of avarice. It is a

long way from Hannibal, Missouri, to Oxford, from the

apprentice pilot on a Mississippi steamer to the scarlet

and gray of the Doctor of Letters of a great and venerable

university, and the record of it, in its final form, will

be an American document of high value.

The free, unconventional life of the

Mississippi Valley of Tom Sawyer's town was an Iliad in

shirt-sleeves, and there was grave question in the minds of

some people whether such a stage of society was a proper

subject for literary presentation; whether it was not too

rudimentary for art. Mr. Howells, who is a humorist of very

delicate and charming quality, has described Hannibal,

Missouri, as "a loafing, out-at-elbows, down-at-heels,

slave-holding Mississippi town;" and Mark Twain's records

amply confirm the general accuracy of this description

loosely applied to a whole section. Mr. James is reported

as saying that one must be a very rudimentary person to

enjoy Mark Twain. This is quite true; as true as that one

must ba a very sophisticated person to enjoy Mr. James.

Provincialism is not a matter of locality but of attitude,

and the provincialism of the Boulevard des Italiens is

quite as pure a product of local ignorance as that of a

frontier mining town. Extreme sophistication and extreme

rudimentariness are alike interesting, significant, and

partial.

In his records of old-time life on the

greatest of American waterways Mark Twain deals with those

facts of experience which, stripped of the accidents of

dress and manners, are the supreme concern of the artist

because they furnish the richest and most suggestive

material. Into the unconventional, lawless, devil-may-care

activity and overflowing high spirits of such a stage of

development only a boy could enter, and in the stories of

Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn Mark Twain has penetrated

to the innermost recesses of that life, and, with its

crudity, profanity, and reckless indifference to

conventions, has made us aware of its wholesome courage,

its gay audacity, its indomitable temper, its contempt for

artificiality, its superstitions, and its homespun idealism

of courage, loyalty, and comradeship. Under an immense

pretension of loafing it was a hard-working life; under an

aspect of overflowing humor it was in dead earnest. Not

until one understands that in the Mississippi Valley humor

was the language of a brave, generous, and laborious people

can one estimate the work of Mark Twain at its true value;

not until one recognizes that the author of "Tom Sawyer" is

a profoundly serious man at heart will he get any real

insight into his significance as a figure in American

literature or into his work as a vital contribution to that

literature.

Mark Twain is not a mere fun-maker, like

Artemus Ward and John Phoenix; he is, in his time and way,

a true humorist--a man, that is, who sees life, not

irresponsibly and superficially, but in its broadest and

most fundamental contrasts. Cervantes, Moliere,

Shakespeare, and Carlyle were great humorists; Gilbert and

Sullivan were fun-makers. It was not lack of seriousness

which made the old-time people of the Mississippi Valley

humorists; it was ease of spirit, surplusage of

cheerfulness, a sense of being on good terms with

Providence in an inexhaustible country, a prevailing

disposition to put a friendly mask on the face of Fate.

This is a fundamental attitude toward life, full of

character, rich in eccentricity of speech and manner,

redolent of that originality and spontaneity which have

always been the joy of the great artists. What rich

adventures of the spirit Shakespeare would have had in the

Mississippi Valley of Mark Twain's boyhood! . . .

|