|

THE town of

Hannibal, Missouri, has had a number of things to

distinguish it during its eighty years of existence:

business men are acquainted with it as the one-time centre

of the largest lumber trade on the Mississippi River; for

lawyers it has furnished some of the most interesting

criminal cases on record; the readers of sensational news

know it as furnishing many opportunities to the lover of

"scare-heads" in journalism; preachers have regarded it for

years as a promising field for evangelistic effort; but

literary people are interested in it chiefly as the boyhood

home of Mark Twain and the scene of his earliest

writings.

It has changed much since Tom Sawyer's

"gang" made things lively for the sleepy little village of

St. Petersburg. The town has reached out until it sweeps

around Lover's Leap on one side and straggles up Holiday's

Hill on the other. Widened, well-paved streets stretch out

to the westward, well set with substantial business houses

and modern dwellings. Walking along these streets you meet

well-dressed women, brisk men, and decorous-looking

children; and there is little to remind you of rollicking,

incorrigible Tom and angular old-fashioned "Aunt Polly,"

who thumped his head and loved him with all the ardor of

her warm old heart.

You say, with a sense of disappointment:

"It is not what it was. The place has changed, and the

people too." But wait a little. Let us walk out Main Street

a few squares. You see that hill rising directly before

you, with what seems to be the remains of an old quarry on

one side and a few clusters of foliage clinging to the

other? It requires a small effort of the imagination to

clothe it once more with original forest. Obliterate the

modern cottages scattered over it, restore the Welchman's

cabin, and you have Holiday's Hill much as it was when Huck

and Tom clambered over it on their way to the Haunted House

to dig for buried treasure.

There to the left is a drug-store. It was

a drug-store fifty years ago, with the same name beside the

doorway, and the same druggist dispensing pills and powders

from behind the same counter. The Hannibal Weekly Journal,

owned and edited by Orion Clemens, was printed for a while

in the rooms over this drug-store; and here, according to

the recent statement of Mr. Samuel Moffett, "the

thirteen-year-old boy served in all capacities, and, in the

occasional absences of his chief, revelled in personal

journalism, with original illustrations hacked on wooden

blocks with a jack-knife, to an extent which riveted the

town's attention, 'but not its admiration.'"

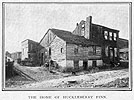

Turn into one of the

cross-streets and look about you. You are in the Hannibal

of fifty years ago, picturesque and unpainted externally,

cobwebby and deserted internally. Walk a short distance out

Hill Street, and you come to the plain little frame house

which was the home of the Clemens family during the greater

part of their residence in Hannibal. Immediately in the

rear of it, on North Street, is a tumble-down shanty which

was the home of Thomas Blankenship, better known to the

public as Huckleberry Finn. Turn into one of the

cross-streets and look about you. You are in the Hannibal

of fifty years ago, picturesque and unpainted externally,

cobwebby and deserted internally. Walk a short distance out

Hill Street, and you come to the plain little frame house

which was the home of the Clemens family during the greater

part of their residence in Hannibal. Immediately in the

rear of it, on North Street, is a tumble-down shanty which

was the home of Thomas Blankenship, better known to the

public as Huckleberry Finn.

One surviving member

of this family remains--a sister of the illustrious Huck.

She seems, however, to be little impressed with the

distinction conferred on the family. When questioned as to

the identity of her brother with Mark Twain's hero, she

said: One surviving member

of this family remains--a sister of the illustrious Huck.

She seems, however, to be little impressed with the

distinction conferred on the family. When questioned as to

the identity of her brother with Mark Twain's hero, she

said:

"Yes, I reckon it was him. Sam and our

boys run together considerable them days, and I reckon it

was Tom or Ben, one; it don't matter which, for both of

'em's dead."

Evidently it was not given to more than

one, in those days, to see the possibilities in a character

like Huckleberry Finn.

"He was nothing more than a plain

reprobate," one of the old "boys" declared. "I knew him,

and I could never see anything picturesque about him. The

principal exploit of his which I now recall is the fact

that he once stole a dearly prized kite of mine. He had

been regarding it with envious eyes for days, and at last,

when he knew I was not at home, he went around and told my

mother that I had sent him for the kite. Of course he got

it, and that was the last I ever saw of it; but I had my

satisfaction"--with a stern, almost ferocious, expression:

"I punched his head!"

Evidently the memory of that theft still

rankles, and renders the judge reluctant to acknowledge the

fine points in a character like Huckleberry Finn,

considered purely from a literary stand-point.

Turning back, you cross Main Street and

come to what was once Water Street. You feel yourself miles

and miles removed from the busy little city, which is still

so close to you that sounds of its cheerful traffic are

plainly audible. Not that this is really what it was, but,

lying there in its desertion and decay, it is very

suggestive of the drowsy, contented life of which Mark

Twain wrote:

"After all these years I can picture that

old time to myself now, just as it was then: the white town

drowsing in the sunshine of a summer morning; the streets

empty, or pretty nearly so, one or two clerks sitting in

front of the Water Street stores, with their

splint-bottomed chairs tilted back against the wall, chins

on breast, hats slouched over their faces, asleep--with

shingle shavings enough around to show what broke them

down; a sow and a litter of pigs loafing around the

sidewalks, doing a lively business in watermelon rinds and

seeds; two or three lonely little freight-piles scattered

about the 'levee,' a pile of 'skids' on the slope of the

stone-paved wharf, and the fragrant town-drunkard asleep in

the shadow of them; two or three wood flats at the head of

the wharf, but nobody to listen to the peaceful lapping of

the wavelets against them; the great Mississippi, the

magnificent Mississippi, rolling its mile-wide tide along,

shining in the sun, the dense forest away on the other

side; the 'point' above town and the 'point' below town,

bounding the river-glimpse and turning it into a sort of

sea, and withal a very still, and brilliant, and lonely

one."

A short distance

below town, lying on this still and shining sea, is a

wooded island which has been known by various names--the

Jackson's Island on which "The Black Avenger of the Spanish

Main" grounded his raft and landed his pirate crew on their

first voyage of adventure and conquest. Since then it has

been called Pete's Island, in honor of the chief of an

older and more formidable band of pirates who had their

rendezvous there. It has also been known as Glasscock's

Island, and at present is Pearl Island. A short distance

below town, lying on this still and shining sea, is a

wooded island which has been known by various names--the

Jackson's Island on which "The Black Avenger of the Spanish

Main" grounded his raft and landed his pirate crew on their

first voyage of adventure and conquest. Since then it has

been called Pete's Island, in honor of the chief of an

older and more formidable band of pirates who had their

rendezvous there. It has also been known as Glasscock's

Island, and at present is Pearl Island.

You are perhaps a traveller, something of

a mountain-climber, so you will not mind the walk to the

top of Holiday's Hill, from which point we have a view of

the river and town, with the wooded shore on the Illinois

side. Let Mark Twain describe it for us, as he comes back

to it after a number of years, with a vision broadened by

travel and experience, and a heart warm with tender

memories:

"It was a Sunday morning, and everybody

was abed yet. So I passed through the vacant streets, still

seeing the town as it was and not as it is, and recognizing

and metaphorically shaking hands with a hundred familiar

objects which no longer exist, and finally climbing

Holiday's Hill to get a comprehensive view. The whole town

spread out before me then, and I could mark and fix every

locality, every detail. Naturally I was a good deal moved.

I said, 'Many of the people I once knew in this tranquil

refuge of my childhood are now in heaven; some, I trust,

are in the other place.'

"From this vantage-ground the extensive

view up and down the river, and wide over the wooded

expanse of Illinois, is very beautiful--one of the most

beautiful on the Mississippi, I think; which is a hazardous

remark to make, for the eight hundred miles of river

between St. Louis and St. Paul afford an unbroken

succession of lovely pictures. It may be that my affection

for the one in question biases my judgment in its favor; I

cannot say as to that. No matter; it was satisfyingly

beautiful to me, and it had the advantage over all other

friends whom I was about to greet again--it had suffered no

change; it was as fresh and comely and gracious as ever it

had been; whereas the faces of the others would be scarred

by the campaigns of life, and marked with their griefs and

defeats, and would give me no upliftings of spirit."

Looking north from Holiday's Hill is a

picturesque bit of country, the bluffs closing about a

narrow gorge, through which flows the stream known in those

days as the Still-House Branch. Here, through long lazy

afternoons, Huck and Tom played Robin Hood, and here was

located the Haunted House where "Injun Joe" found the

buried treasure. We may believe this but little changed. A

few houses cluster about the opening at the railroad, and

as we stop to make some inquiries about localities a

barefooted boy with a dilapidated hat two sizes too large

for him comes and leans against the fence and regards us

with frank, unflattering eyes. Another joins him, and we

hear them addressed as "Buck" and "Bill." Seeing no

prospect of diversion, they vault over the low board fence

and disappear in the bushes which skirt the hill-side.

After all, we think, localities may

change, but human nature, if let alone, remains about the

same. We may build fine houses, and dress and groom, and

prune and train, until we succeed in raising up a

generation of children looking like fashion plates and

acting like little old men and women, but give it half a

chance and it springs up into the same rollicking, untamed

creature of luxuriant fancy and inexhaustible resources as

the two boys who have been the emulation and delight of

several generations of children.

Perhaps this explains, in some degree, the

unfailing interest which still attaches to these early

books of Mark Twain. Other writers have given us excellent

studies of human nature--of child nature--but the types are

imperfect, and so wrought about by peculiarities of style,

national characteristics, and a thousand and one things, as

to make a critical literary taste necessary to their full

appreciation. Not so in this case. Mark Twain has given us

not the boy of the Mississippi Valley as he was fifty years

ago, but a broad type which finds ready interpreters in

every nook and corner of the nation and in every passing

generation.

About two miles

below town is the cave in which Tom had some of his most

thrilling adventures. The opening lies well back in the

side of a hill, with a pretty park and athletic ground

around it, which are in frequent use for picnics and ball

games. Passing inside, you thread the same labyrinth of

narrow corridors, with rifts dropping off at your feet as

if into the very bowels of the earth. Here is the spring of

clear, cold water where Tom and Becky sat down to watch

their last bit of candle go out, leaving them in dense and

utter darkness. There is the corridor known as "Bat Alley,"

where myriads of those creatures cling to walls and

ceiling, and, disturbed by the light of your torch, beat

about your head in a manner far from comfortable. About two miles

below town is the cave in which Tom had some of his most

thrilling adventures. The opening lies well back in the

side of a hill, with a pretty park and athletic ground

around it, which are in frequent use for picnics and ball

games. Passing inside, you thread the same labyrinth of

narrow corridors, with rifts dropping off at your feet as

if into the very bowels of the earth. Here is the spring of

clear, cold water where Tom and Becky sat down to watch

their last bit of candle go out, leaving them in dense and

utter darkness. There is the corridor known as "Bat Alley,"

where myriads of those creatures cling to walls and

ceiling, and, disturbed by the light of your torch, beat

about your head in a manner far from comfortable.

The small stream known as Bear Creek, "so

called, perhaps, because it was always so particularly bare

of bears," skirts the town on the south side, and

notwithstanding his statement that only an expert can find

it, a number of present-day boys are intimately acquainted

with all the swimming-holes, and Mark Twain's personal

experience is frequently repeated: "I used to get drowned

in it regularly every summer, and be drained out and

inflated and set going again by some chance enemy, but not

enough of it is unoccupied now to drown a person in. It was

a famous breeder of chills and fever in my day. I remember

one summer when everybody in the town had the disease at

once. Many chimneys were shaken down, and all the houses so

racked that the town had to be rebuilt."

The shabby little

brick church where the children of that day attended

Sunday-school, and suffered through the eternity of a long

Presbyterian sermon, is now used as a court-house. We have

it on good authority that the picture of the painfully

clean boy standing at the door of this church on Sunday

morning, trading licorice, fish-hooks, and marbles for

tickets of various colors and values, and through this

traffic obtaining the distinction of a prize pupil,

notwithstanding the fact that he was never known to recite

two verses, not to mention two thousand, is in no respect

overdrawn. The boys and girls who attended that school also

recall vividly the superintendent, a man named Cross, to

whom they affectionately referred as "Cross by name and

cross by nature." The shabby little

brick church where the children of that day attended

Sunday-school, and suffered through the eternity of a long

Presbyterian sermon, is now used as a court-house. We have

it on good authority that the picture of the painfully

clean boy standing at the door of this church on Sunday

morning, trading licorice, fish-hooks, and marbles for

tickets of various colors and values, and through this

traffic obtaining the distinction of a prize pupil,

notwithstanding the fact that he was never known to recite

two verses, not to mention two thousand, is in no respect

overdrawn. The boys and girls who attended that school also

recall vividly the superintendent, a man named Cross, to

whom they affectionately referred as "Cross by name and

cross by nature."

In searching for boyhood friends and

companions of Mark Twain we are reminded of the condition

of things in the village of St. Petersburg immediately

after the supposed drowning of Tom Sawyer and Joe Harper,

when disputes arose as to who saw the dead boys last in

life, and those who could establish such claim "took to

themselves airs of sacred importance."

"One poor chap, who had no other grandeur

to offer, said, with tolerably manifest pride in the

remembrance,

"'Well, Tom Sawyer, he licked me

once!'"

"But that bid for glory was a failure.

Most of the boys could say that much, and so it cheapened

the distinction too much."

By all odds the most interesting character

connected with the history of those years is Mrs. A. L.

Frazer, formerly Miss Laura Hawkins, presumably the Becky

Thatcher of Tom Sawyer, and the Laura Hawkins of The Gilded

Age. A very gentle and winsome lady she is, with wavy gray

locks about her face, eyes as sparkling as any girl's, and

a charm of manner which marks the genuine woman, no matter

what station in life may claim her. Mrs. Frazer enjoys

talking about her old play-mate, not because he has grown

great and famous, but because he was her old play-mate. Her

heart warms to the memory of those halcyon days, and in her

regard there mingles no questioning of the world's

opinions, no weighing of possible honors. It is one of

those tender and unselfish friendships which some very

lovable women are capable of inspiring and cherishing

through a long lifetime.

"I remember very

well when we moved into the house opposite where Mr. John

M. Clemens lived," she said. "I remember also the first

time I ever saw Mark Twain. He was then a barefooted boy,

and he came out in the street before our house and turned

hand-springs, and stood on his head, and cut just such

capers as he describes in Tom's 'showing off' before Becky.

We were good friends from the first. One of our favorite

play-places was in the Clemens yard, where we built houses

out of a heap of bricks. On one occasion he accidentally

tumbled our house down on my hand and made blood blisters

on every finger. "I remember very

well when we moved into the house opposite where Mr. John

M. Clemens lived," she said. "I remember also the first

time I ever saw Mark Twain. He was then a barefooted boy,

and he came out in the street before our house and turned

hand-springs, and stood on his head, and cut just such

capers as he describes in Tom's 'showing off' before Becky.

We were good friends from the first. One of our favorite

play-places was in the Clemens yard, where we built houses

out of a heap of bricks. On one occasion he accidentally

tumbled our house down on my hand and made blood blisters

on every finger.

"On another occasion a crowd of boys and

girls went out on the hills of what is now Palmyra Avenue,

to spend a Saturday afternoon. The hill-sides were covered

with trees and brush, and a favorite sport was to bend down

slender saplings and ride, the smaller girls being taken on

behind the larger ones. I was having a fine ride behind one

of the big girls when she suddenly sprang off, and I was

thrown to the ground, striking my head against a stone. I

was taken home unconscious, and was very ill for some time,

and I remember hearing the children talk about how scared

and anxious 'Sam' was."

We can but wonder if it was this illness

which so wrought on Tom's health and spirits, and if it was

his own condition which he so feelingly describes as he

tells of the boy hanging around the gate of the school-yard

anxiously watching for the coming of Becky: "Presently Jeff

Thatcher hove in sight, and Tom's face lighted; but he

gazed a moment, then turned sorrowfully away. When Jeff

arrived, Tom accosted him and 'led up' warily to

opportunities for remark about Becky, but the giddy lad

never could see the bait. Tom watched and watched, hoping

whenever a whisking frock came in sight, and hating the

owner of it whenever he saw she was not the right one. At

last frocks ceased to appear, and he dropped down into the

dumps; he entered the empty school-house and sat down to

suffer. Then one more frock passed in at the gate, and

Tom's heart gave a great bound. The next instant he was out

and 'going on' like an Indian, yelling, laughing, chasing

boys, jumping over fences at the risk of life and limb,

throwing hand-springs, standing on his head, doing all the

heroic things he could conceive of, and keeping a furtive

eye out all the while to see if Becky Thatcher was

noticing."

If others in the town were unable to see

Huck Finn with Mark Twain's eyes, the same difficulty did

not obtain in this case, for his little sweetheart seems to

have been a universal favorite. One of the old "boys" tells

the story of how on one occasion three of the "gang"

started out into the great world to seek their fortune,

with the understanding that on their return one of the

number should marry Laura Hawkins. How the lucky one was to

be chosen he fails to relate, but it is safe to say that if

the matter had come to settlement after the manner in which

boys usually adjust difficulties, Mark Twain would have had

at least "a fighting chance." But alas for the brave

knights! When they returned the princess was gone! She

might have been carried off in their absence by a dreadful

ogre, or a rival prince might have spirited her away to his

castle, but the unpoetical fact was that her father had

moved away, and that was the end of this little

romance.

On the event of his marriage, Mark Twain

enclosed a card to the brother of Mrs. Frazer, and on the

inner cover was written:

Mrs. ----- (married name unknown to

me).

(Formerly Miss Laura Hawkins, first

sweetheart of one of the within named parties 29 years ago.

Pardon the suggestive figures.)

On the sloping hill-sides of beautiful

Mount Olivet are to be found as many friends and boyhood

companions of the great humorist as walk the streets of the

busy little city two miles away. Here on the very summit,

where a rift in the foliage on intervening hills opens a

view of the great, placid, shining river, is the lot with

its simple head-stones where the greater part of the

Clemens family are sleeping. There is John M. Clemens, the

kindly, dignified, if somewhat unfortunate father, about

whom one hears only the tenderest and most respectful

reminiscences; next to him the mother, from whom her

distinguished son is said to have inherited some of the

traits which have made him famous; Henry Clemens, the

younger brother, who lost his life in a steamboat explosion

at Memphis; and last in the row, Orion Clemens, the elder

brother, under whose tutelage Samuel Clemens began his

literary career.

In his recent biographical sketch, Mr.

Samuel Moffett says:

"Native character will always make itself

felt, but one may wonder whether Mark Twain's humor would

have developed in quite so sympathetic and buoyant a vein

if he had been brought up in Ecclefechan instead of in

Hannibal, and whether Carlyle might not have been a little

more human if he had spent his boyhood in Hannibal instead

of in Ecclefechan."

Without claiming an intimate knowledge of

the facilities afforded by Ecclefechan for the development

of native character, we venture the belief that not

Ecclefechan nor any other locality could have furnished

better facilities for the untrammelled development of this

native genius than it enjoyed in Hannibal.

Before all and above all, Mark Twain is a

great interpreter of human nature--not the groomed and

polished species of the drawing-room, but the unpruned and

untrained article which grew up spontaneously in such

congenial soil as Hannibal afforded fifty years ago. Call

it fatalism or faith, but circumstance, or Providence,

usually places within a man's reach just the facilities

necessary for the making of his individual character and

the accomplishment of his peculiar work. Not all the

universities in all the land could have done so much for

Mark Twain as did the contact with primitive life and

character in this river town, and the later and wider

experience of a pilot on the Mississippi River.

|